eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Kyeongjin Park

, Hyeon Chul Kim

, Eun Hye Lee

, Kyungdoh Kim

10.5143/JESK.2017.36.3.197 Epub 2017 June 24

Abstract

Objective: We propose to apply color information to facilitate finding books in the library.

Background: Currently, books are classified in the basis of a decimal classification system and a call number in the library. Users find a book using the call number. However, this classification system causes various difficulties.

Method: In a process analysis and survey study, we identify what the real problem is and where the problem is occurred. To solve the real problems, we derived a new search method using color information. We conducted a comparative experiment with 48 participants to see whether the new method can show higher performance.

Results: The new method using color information showed faster time and higher subjective rating scores than current call number method. Also, the new method showed faster time regardless of the skill level while the call number method showed time differences in terms of the skill level.

Conclusion: The effectiveness of the proposed method was verified by experiments. Users will be able to find the desired book without difficulty. This method can improve the quality of service and satisfaction of library use.

Application: Our book search method can be applied as a book search tool in a real public library. We hope that the method can provide higher satisfaction to users.

Keywords

Color information Call number Library Process analysis Book search

Thompson (1983) predicted in "The End of Library" that the roles that books played would be replaced with those of computers, and that as a result, book-centered libraries would disappear. Libraries, however, are still important institutes in the society that provide everyone with necessary information and data as a social welfare system that functions as a pivot of the local community network (Park, 2012). As they play key roles in information delivery, the demands for libraries continue increasing in reflection of the intellectual level of people that is going up. According to the data provided by the National Statistics Library System in 2015, the number of public libraries including private libraries is 786 as of 2011, and it continues increasing year after year (National Library Statistics System, 2016).

Particularly, university libraries provide university members with education, learning, and research functions at the university level. As abilities to explore and utilize information effectively are required, university libraries play important roles as a medium for information search (Jung and Kwon, 2013). According to Yoon (2007), as the numbers of materials, periodical subscriptions, material purchasing prices at libraries among 330 OECD member countries are large, the number of SCI papers is large accordingly. The same study indicates that the correlation rate of the numbers of papers, materials, and periodical types is as high as 0.9. Luther (2008) also reported that one dollar investment into a university library results in creation of external research fund as much as 4.36 dollars. As such studies indicate, university libraries play important roles as an infrastructure for academic research data as well as a fundamental education facility. The number of domestic university libraries including those in colleges and graduate schools continues increasing every year (National Library Statistics System, 2016).

While digital information distribution via the Internet is active recently, university libraries still invest a lot of resources into collection mainly of printed materials. Although there may be some difference depending on the university library scale, the increase of library collection is distinct in every library. According to statistics of university libraries reported by the National Library Statistics System, the number of books per library hall continued increasing up to 2015. It reached 334,826 volumes in 2015 (National Library Statistics System, 2016).

As the number of books increases continually, the necessity of keeping and managing books at university libraries systematically is also emphasized. Hjorland (2012) pointed out that book classification is essential for a library classification system, and that such classification systems need to reflect the characteristics of the digital era. Currently, book numbers are used to classify volumes efficiently. Bliss (1910) also emphasized that without book numbers, it would be challenging to find a desired book at a library. Satija (1993) stated that without book numbers, it would take longer time to arrange books, for users to find books on book shelves, and to take steps of renewing book bending. In addition, Chang and Chung (2013) found that among papers published through domestic journals in the area of library and information science between 1986 and 2011, 4.9% were related to book classification and symbol systems. Cho (2004), however, pointed out that as the book stock continues increasing, the current library symbol system involves problems in terms of symbol duplication, efficiency of book management, compatibility with other libraries, etc. According to Cho, for a library user to collect desired data, he or she needs to approach a bookshelf, and in this process, a standardized book symbol system is essential for efficient management.

In Korea, libraries classify books in application of Dewey Decimal Classification System. Dewey Decimal Classification System (DDC) was designed by Melville Dewey in 1873 to classify books at the library of Amherst College, the U.S. This system categorize books into academic areas (Dewey, 1958). Based on Dewey Decimal System, librarians classify books according to their book classification manuals and designate call numbers. Call numbers consist of 4 elements (local symbol, classification symbol, book symbol, and additional symbol).

This classification method, however, may cause difficulties when library users have to search for certain books (Lynch and Mulero, 2007; Raymond, 1998). Since Dewey Decimal Classification System searches for books based on academic areas, it may fail reflecting the context of library users' search intent (Baker and Shepherd, 1987). Besides, users may not be familiar with categorizing symbols. Lee (2013) as well pointed out that it would be difficult for someone who uses a library for the first time to find certain materials by using the classification system without help from others. As stated by Park et al. (2003), it requires a lot of time in reality for someone who rarely uses a library to find a certain book for himself/herself by using such book lending procedures particularly in a university library which maintains hundreds of thousands of books. Just a few librarians who classify and arrange books may know what types of books are in which bookshelves and bookrooms while ordinary users have to spend a lot of time in finding one certain book that they are looking for. For instance, Yoo (2004) analyzed 474 inquiries from library users at Duksung Women's University for 64 days from October 10, 2000, and among these, 29.3% were about location of certain books.

To address above-mentioned challenges, a number of researches have suggested alternatives (Lee, 2013; Jung et al., 2013; Chung and Lee, 2009). To improve the process of finding books using existing call numbers, Lee (2013) suggested the following: bookshelf labeling; 7 different familiar colors of a rainbow; locating books by using alphabets with above colors at the side of each bookshelf; indicating numbers for the rows and brightness for lines of each bookshelf; and locating books by using combinations of these numbers, colors, and brightness. If the library is extraordinarily large, however, two or three colors may be used more than once on the same floor of bookshelves that are supposed to be of one color. As more colors are added, it becomes difficult to distinguish one from another intuitively. Jung et al. (2013) suggested to designate the same color for both the book's call number and the bookstand for it and to attach paper of the same color to bookshelves in the same category. This supplementary means to call numbers could shorten the time of finding a certain book. Jung et al. also suggested to provide library drawings on which call numbers and book locations are indicated and to use smart phone applications and QR codes. Chung and Lee (2009) suggested to utilize collection codes and call number simplification methods that help children approach library data conveniently. However, these classification systems based on the use of Korean characters, numbers, and English words for users' intuitive understanding have limitations in differentiating themselves from existing classification methods.

Hence, this study examines how actual users evaluate the library book searching process in order to grasp specific steps that may cause difficulties in finding books at a library based on a survey conducted among those who have used libraries. In reference to the results of the survey and process analysis, a method to improve the library book searching process that can address above-mentioned problems is proposed. Finally, the effect of the suggested method is verified by comparing it with existing methods through an experiment in an actual library.

2.1 A process analysis

Currently, most libraries provide users with location information of books in an Internet-based mode (Jung et al., 2013). Users can search for a book by using a computer at the library or a personal mobile device, and the library website provides book call numbers. Users can find a book in reference to the call number that contains location information.

Table 1 shows a work flow process based on the book-search process analysis at a library. An experiment was conducted at Hongik University library, and advance interviews were conducted among 6 participants to ask if they were familiar with using call numbers at a library. They were then divided to Group A and Group B depending on the level of familiarity. Group A included 3 participants who were familiar with finding books in reference to given call numbers while Group B included 3 who were not familiar with that process. The times that Group A members had used a library were 9.7 on average while the times that Group B had used a library were 1.3 on average. Participants were provided with 2 books out of 6 arranged at bookshelf No. 800 (Literary) and asked to locate them. The time was measured 12 times in total, and the process time of participants was 456.3 seconds on average, and the deviation was 75.51 (Table 1).

As the 'average time / total average time' in each step were expressed as a percentage, the top three steps that took much time were the same. These top 3 processes were No. 4, 8, and 9. In Group B, No. 9 process accounted for 57.32% in among the processes. The average time that the unfamiliar group took to find a given book in reference to the call number was shorter than that of the familiar group.

Tasks in finding a book on a bookshelf that took more time than others were divided into 2 steps, and then the time that each task took was measured. Once a library user arrives at a bookshelf, the book search process is divided into the following 2 steps: finding the block where the desired book is arranged; and then finding the book in the block. However, the distinction between these two steps is vague, and thus the time that a user is notified of the block and finds the book there is measured instead (Table 2).

|

9 |

Finding book in shelf |

Group A |

Group B |

|||||||

|

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

|||||||

|

9-1 |

Finding block |

● |

▷ |

□ |

Ⅾ |

▽ |

153.2 |

23.13 |

282.3 |

28.57 |

|

9-2 |

Finding book in block |

● |

▷ |

□ |

Ⅾ |

▽ |

18 |

3.06 |

20.5 |

3.77 |

When the experiment participants were notified of the book block, the time taken to find that book was shortened. In this case, Group A took 18 seconds and Group B 20.5 seconds, which is insignificant difference, and this result indicates that the general time was far shorter than that of finding the block and then the book. In other words, this process analysis shows that the task taking most time in finding a book at a library is to find the block where the desired book is arranged.

2.2 A survey study

From April 8 to April 15, 2016, a survey was conducted among 129 Hongik University students who had used Hongik University Central Library (Mean age: 24.5, SD: 1.81) on book search at the Central Library.

It turned out that most of the respondents would use the library only when there was a book that they needed (89%). Among them, many would use the library irregularly when necessary (57%). Only 27% of the respondents felt satisfied with the current library book search process in reference to call numbers. Additional comments included the following negative opinions: 'It is difficult to find a book only with symbols'; and 'it is so complicated that I could not distinguish at one glance, and the guideboard does not indicate clearly the order of alphabets and Korean characters in the symbols, which is unsatisfactory.'

Table 3 and Table 4 show the level of difficulty that respondents felt in finding the designated books at the library only with the classification symbols when they referred to the symbols only once or a few times. The percentage of respondents who felt easy to find books in reference to call numbers was quite low. The survey result shows that after using the classification symbols, the users felt less difficult in finding books. However, it was thought that respondents would use the library irregularly only when it was necessary. Thus, although the level of difficulty in finding a book by using call numbers might decrease as users become more familiar with them, the possibility is low in consideration of their use patterns. Additional comments included the following opinions: 'I still feel unfamiliar after using several times'; and 'I felt difficult to understand what the symbols meant.' More than half of the comments collected among respondents were about their being unable to understand the call numbers themselves. In other words, it turned out that the way of library book search in reference to call numbers was not appropriate for most users who come to the library intermittently, and the level of satisfaction was low. understandability of call numbers itself was low among users, and they felt difficult to apply call numbers in the process of finding books. Even after a number of tries, the feeling of difficulty was not improved significantly.

Hence, the results of the process analysis and survey indicate that the current call number method needs to be improved, and that there needs to be an approach to locating the book block.

|

|

Frequency (%) |

|

Very difficult |

16 (12%) |

|

Difficult |

43 (33%) |

|

Normal |

54 (41%) |

|

Easy |

10 (7%) |

|

Very easy |

6 (4%) |

|

|

Frequency

(%) |

|

Very difficult |

6 (4%) |

|

Difficult |

31 (27%) |

|

Normal |

64 (49%) |

|

Easy |

18 (13%) |

|

Very easy |

10 (7%) |

Amheim (1954) states that colors and shapes provide visual information and are of expressivity, and that the expressivity of colors is better than that of shapes. According to Cho (2010), it is possible to communicate fast and precisely when specific information on the target is provided with colors in addition to other visual expressions. Providing information with colors is effective and help for humans' acceptance of information. In addition, Kwon and Kim (2011) point out that color is is one of the quite effective means in the cost-profit perspective and in terms of exchange of visual information.

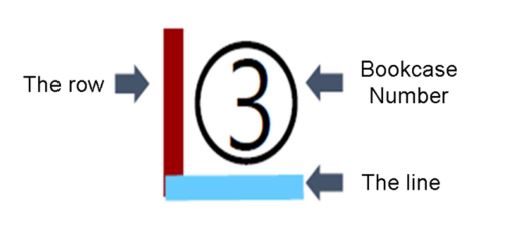

This study utilizes color information which is advantageous in various aspects as an alternative to existing book-locating methods that are based on call numbers. Most of the other researches that suggest solutions to the same problem (Lee, 2013; Jung et al., 2013; Chung and Lee, 2009) consider using color information in utilization of surfaces of a bookshelf that have not been used yet. A bookshelf has its vertical and horizontal surfaces that divide blocks, and these surfaces are sufficient to represent color information. As the location of a book is indicated by color information that represents the row and line of the bookshelf, it is easy to find the block where the book is arranged. When a user searches for a book, the color information is provided as in Figure 1. The numbers provide information of the bookshelf with the desired book, and the Korean consonant 'ㄴ' notifies a user of the location of the block where the desired book is arranged. The vertical part indicates the line of the bookshelf, and the horizontal part the row of the bookshelf.

Figure 2 shows the library book search process by means of color information as suggested in this study. Users can search for a book and be given its color information (Step 1). The provided color information includes numbers in a circle that indicate the shelf and the location of the row and line of the bookshelf that contains the desired book. Users can find the bookshelf in reference to the numbers (Step 2), and then they can find the block where the book is located in reference to color information (Step 3). After arriving at the block, users can look through the existing call numbers or book titles to find the book. Call numbers are useful and effective in terms of book management at every library. Thus, it is difficult to remove or modify such symbols in reality. Instead, existing call numbers may be utilized as a supplementary tool to locate a book in a block. After all, users can locate a book by referring to the title instead of the call number. When such color methods are to be introduced for system improvement, those with color vision deficiency, who account for 12% of the entire population, also need to be taken into consideration. According to Connor (2011), there are 3 aspects of color design to be considered for color vision defectives. First, color combinations that color vision defectives hardly distinguish (green & red, green & brown, blue & purple, green & blue, yellowish green & yellow, blue & gray, green & gray, and green & black) need to be avoided. The second consideration is a design with different brightness levels for each color, which is effective for color vision defectives. The third consideration is to make good use of color contrast since even color blinds are able to distinguish colors to some extent. Thus, using red and blue of clear color distinction is recommended. In addition, color information may be more specified by changing the level of brightness. Figure 3 below shows an example of a bookshelf to which color information is applied.

4.1 Experiment environment

An experiment was conducted at the Literary section (800) of Seoul Campus Central Library, Hongik University. The Literary section (800) keeps the largest volume of books among sections of Hongik University Central Library, and this is the same with most other large-scale libraries. The Literary section consists of 4 7-line 2-column bookshelves. These bookshelves have 8 horizontal blocks and 7 vertical blocks, 56 blocks in total, on which an experiment was conducted.

4.2 Subjects

48 Hongik University students participated in the experiment. The average age was 22.8, and the standard deviation was 1.87. 24 individuals among the participants were asked to find the designated books in reference to call numbers. 12 out of these participants had used the library at least 10 times before and were familiar with finding books in reference to call numbers. The rest 12 were unfamiliar with finding books in reference to call numbers and had rarely used the library. The other 24 were asked to find books in reference to color information. All of the 24 individuals were given sufficient explanation on how to find books in the library by means of color information. 12 out of these 24 were given at least 4 opportunities to practice finding books by means of color information prior to the experiment.

4.3 Independent variables

4.3.1 Search method

An experiment was conducted to compare the color-based library book search method suggested in this study with the existing method in reference to call numbers. To realize color information presentation, colored paper was attached on bookshelves. Figure 4 shows bookshelves with color information on them.

4.3.2 Skill level

In the process analysis, the time to find a book was shortened as the times of using the Central Library increased. Hence, it was sought to examine the effect of the skill level on the process of finding books. The average times of experiencing library book search service among the group who were familiar with finding books in a library by using call numbers were 9.6. Participants who had used the Central Library in reference to call numbers at least 10 times were defined as 'Advanced Beginners,' and those who had used it less than 10 times were defined as 'Novices.' In addition, participants who had experienced at least 4 times after listening to explanation on color information were defined as 'Advanced Beginners,' and those who found designated books with no advance practice were defined as 'Novices.'

4.4 Procedure

The experiment was designed between subjects: 24 participants were given a task to find 4 randomly designated books from the bookshelves with color information on them. The rest 24 participants were given a task to find books only in reference to call numbers. 4 different book locations were designated on the basis of the distance from the starting point and the distance from the eye level. Participants were to recognize books to find and notify subjects of the beginning of book search. Subjects were to measure and record the time participants took to find the books. Once the experiment of finding 4 books was completed, a questionnaire was to be prepared before the experiment came to its end. The order of books to be found was designated randomly and evenly in consideration of book locations, heights, and distances.

4.5 Dependent variables

4.5.1 Completion time

Participants had subjects measure the time of exploring books to find the designated ones. The average time taken to find 4 books was measured on a scale of seconds to two decimal places. The basic stopwatch application installed in Samsung Galaxy S5 was used.

4.5.2 Subjective ratings

According to the survey result, the level of satisfaction with the book search method in reference to call numbers was not high among users. understandability of how to find a book by using call numbers was low as well. This result shows that using call numbers itself was viewed as difficult and negative among library users and thus to be improved. According to comments in the survey regarding these three aspects, many found using call numbers difficult and felt hard to apply the book search process even if they understood call numbers. Accordingly, dependent variables of understandability and easiness were selected.

After the book search task, participants were asked to fill in the questionnaire of overall satisfaction with the book search method, and the 7-point Likert-type scale was applied to this questionnaire. To the question, "Are you satisfied with this book search method?", Point 1 indicates 'very unsatisfied' and Point 7 indicates 'very satisfied.' The higher score, the higher level of satisfaction. The level of easiness of the book search method was also evaluated in the 7-point Likert-type scale. The question - "How much difficult was the book search method to you?" - was to evaluate the level of easiness that subjects felt about the book search method in reference to color information that this suggests in comparison with call numbers. The higher score, the easier the search method. Additionally, Participants were asked to evaluate understandability of the book search method in the 7-point Likert-type scale. The question - "Do you feel hard to understand the book search method?" - was to ask subjects' understanding of the book search method by means of color information in comparison with call numbers. The higher score, the higher level of understandability of the book search method.

Data was collected from 48 individuals, and all of it was utilized in the analysis with no missing values. Based on the experiment result, Shapiro-Wilk normality test was conducted: p-value was at least .05, which indicates that the normality requirement was met (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965). Two-way ANOVA test was additionally conducted.

5.1 Completion time

5.1.1 Main effect

The difference in completion time between the color information based method and the call number method turned out to be significant (F1,42 = 347.08, p < .001). When the book search method in reference to color information suggested in this study was used, the completion time was shortened as much as 172.1 seconds on average. Table 5 shows the statistics of the experiment result. When color information was used in book search, the time was significantly reduced.

|

Dependent variable |

Search method |

Mean |

SD |

F |

p value |

|

Completion time |

Color information |

41.1 |

56.40 |

347.08 |

< .001 |

|

Call number |

213.2 |

9.22 |

The average difference in time of finding 4 books depending on the book search skill turned out to be significant (F1,42 = 12.35, p < .001). It turned out that skillful ones would find books faster. Table 6 shows statistics of the experiment result.

|

Dependent variable |

Skill level |

Mean |

SD |

F |

p value |

|

Completion time |

Advanced beginner |

110.9 |

76.24 |

12.35 |

< .001 |

|

Novice |

143.4 |

111.17 |

5.1.2 Interaction effect between the search method and skill level

The interaction between the book search method and the search skill turned out to be significant in relation to the time of finding books (F1,42 = 16.96, p < .001). Figure 5 shows the interaction in graph. When call numbers were used, there was difference between advanced beginners and novices (MAdvanced Beginner = 178.0 < MNovice = 248.5, p < .001). When color information was used to find books, in contrast, there was no difference between advanced beginners and novices (MAdvanced Beginner = 43.9 > MNovice = 38.3, p = .14). In other words, the book search method by means of color information was effective in reducing the time regardless of the search skill.

5.2 Subjective ratings

5.2.1 Main effect

The effect of satisfaction with the book search method, easiness, and understandability was statistically significant. When the color information method was used, it was evaluated as positive in every subjective index (F1,42 = 70.882, p < .001, F1,42 = 93.25, p < .001, F1,42 = 93.25, p < .001). Table 7 shows related statistics.

|

Dependent variable |

Way of searching book |

Mean |

SD |

F |

p value |

|

Overall satisfaction |

Color information |

5.8 |

.68 |

70.88 |

<.001 |

|

Call number |

3.0 |

1.41 |

|||

|

Easiness |

Color information |

5.6 |

.65 |

93.25 |

<.001 |

|

Call number |

2.7 |

1.30 |

|||

|

Understandability |

Color information |

6.0 |

.81 |

47.78 |

<.001 |

|

Call number |

3.6 |

1.41 |

5.2.2 Interaction effects between the search method and skill level

The interactive effect of the book search method and the search skill on the level of satisfaction was insignificant (F1,42 = .07, p = .80). When call numbers were used, the effect of the search skill on the level of satisfaction was insignificant (MAdvanced Beginner = 2.9 < MNovice = 3.1, p = .78), and when color information was used as well, there was no difference in the level of satisfaction with the book search method (MAdvanced Beginner = 5.8 = MNovice = 5.8, p = 1). When color information was used to find books, the level of satisfaction was high regardless of the skill level. When call numbers were used, the level of satisfaction was low regardless of the skill level. In other words, the level of satisfaction was high when the book search method by means of color information regardless of the search skill level. The survey and experiment results show that as the level of skill was high, it contributed to shortening the book search time, but in the case of call numbers, the difference seemed not enough to effect the level of satisfaction. Figure 6 shows the results in graph.

In addition, the interactive effect of the search skill and search method on participants' easiness and understandability was insignificant (F1,42 = .08, p = .78, F1,42 = .24, p = .62). When call numbers were used, the effect of the skill level on the level of easiness was insignificant (MAdvanced Beginner = 2.6 < MNovice = 2.8, p = .65), and likewise, when color information was used, there was no difference in the level of easiness of finding books (MAdvanced Beginner = 5.6 < MNovice = 5.7, p = .76). In other words, when color information was used in book search, the level of easiness was high regardless of the search skill level. When call numbers were used for book search, the level of difficulty in finding books that advanced beginners felt whose book search time was relatively short was similar to that of novices (the level of easiness was low). When call numbers were used, the difference in understandability depending on the skill level was insignificant (MAdvanced Beginner = 3.6 < MNovice = 3.7, p = .89). Likewise, when color information was used, there was no difference in understandability of book search (MAdvanced Beginner = 6.1 > MNovice = 5.8, p = .46). This result suggests that when call numbers were used for book search, the level of difficulty that users feel was high, and even call numbers themselves were quite difficult. When the color information method proposed in this study was used, in contrast, there was significant improvement in these aspects regardless of the skill level. This method is easy-to-understand even among less experienced individuals, and the method itself is easy. Figure 7 shows the results in graph.

This study examines the existing library book search method by means of call numbers and suggests a new method that utilizes color information. To analyze the problem accurately, a preliminary study was conducted, and a survey was conducted among library users. The results show that users would spend most time in finding the block where the desired book was located. While there have been a number of researches on the same research subject (Lee, 2013; Jung et al., 2013; Chung and Lee, 2009), these studies are not enough specifically to address the bottleneck. Jung et al. (2013) suggested a way of using color information by attaching paper of different colors on bookshelves depending on the category, but this method either failed to address the bottleneck of the book search process which is the main objective of this study.

The survey was conducted to examine subjective elements of users in finding books at a library in reference to call numbers. Users found call numbers difficult, and their understandability of how to use this method was low as well. Hence, the level of satisfaction turned out to be low.

In the experiment conducted to compare the book search methods, the library book search method in reference to color information, which is suggested in this study, contributed to reducing the search time as much as 80.72% regardless of the skill level. this color information method improved all of the level of satisfaction, easiness, and understandability. The interactive effect of the skill level and the book search method on three subjective indexes was all insignificant. Among the presented independent variable, the subjective indexes were found to be affected only by the book search method. In addition, while the existing method (call numbers) showed difference in the search time depending on the skill level, it turned out in the experiment that the skill level did not affect subjective aspects. Particularly in the book search in reference to call numbers, highly skillful participants found books fast, but the difference from novices in terms of symbols was insignificant. In addition, both groups found call numbers themselves difficult, and there was no significant difference in the level of satisfaction. Hence, the findings of this study clarify that while the book search method by means of call numbers may shorten the search time as use experience is accumulated, this method fails addressing subjective indexes of users regardless of experience. This clearly indicates the necessity of improving the current book search method. The library book search method by means of color information, which is proposed in this study, shortens the book search time and improves subjective indexes of users as verified by the comparative experiment.

This study involves some limitations: The library designates call numbers in accordance with specified rules. As the number of books continues growing, old books may be disposed or kept in a separate space of storage. In case that books are disposed or added, specific ways to add color information accordingly and efficiently need to be adopted. In addition, since color information is to be introduced to the entire library in the initial stage, the initial cost may not be covered by the general operating cost.

The existing book search method based on call numbers has caused inconvenience among users a lot. The proposed method in this study can make it easier and more efficient to locate books than the existing method while it is difficult to modify all the call numbers used for the book classification system at libraries around the country. Therefore, the present study proposes to apply this library book search method in reference to color information practically in libraries. To this end, it is necessary to estimate the initial costs and analyze the expected effect and benefit. In addition, efforts need to be put forth into finding out efficient ways to address the difficulty of introducing color information to each block.

References

1. Arnheim, R., Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye. Univ of California Press, 1954.

Crossref

Google Scholar

PubMed

2. Baker, S.L. and Shepherd, G.W., Fiction classification schemes: the principles behind them and their success, RQ, 27(2), 245-251, 1987. ISSN: 0033-7072

Crossref

Google Scholar

3. Bliss, H.E., A Modern Classification for Libraries: With Simple Notation, Mnemonics, and Alternatives, Library Journal, 35, 351-318, 1910.

Crossref

4. Chang, Y.M. and Chung, Y.K., A Study on Analysis of Research Trends about Classification in Korea, Applied Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 24(1), 25-44, 2013.

Crossref

Google Scholar

5. Cho, J.K., The study on the color of mobile application thru methodology. Journal of Design Communication, 33(1) 98-107, 2010.

Crossref

6. Cho, Y.H., The Survey of Actual Condition on Improvement and Point at Issue of Currently Book Numbers in Korean University Libraries, Journal of the Korean Society for Information Management, 21(4), 233-249, 2004.

Crossref

Google Scholar

7. Chung, Y.K. and Lee, M.H., A Study of Simplifying Call Numbers with Collection Codes at Children Libraries. Journal of the Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 20(1), 23-38, 2009.

Crossref

Google Scholar

8. Connor, Z., Colour psychology and colour therapy: Caveat emptor, Color Research and Application, 36(3), 229-234, 2011.

Crossref

Google Scholar

9. Dewey, M., Dewey decimal classification, Latest ed., The Forest Press, 1958.

Crossref

Google Scholar

10. Hjorland, B., Is Classification Necessary after Google?, Journal of Documentation, 68(3), 299-317, 2012.

Crossref

Google Scholar

11. Jung, M.J. and Kwon, N.Y.,

Crossref

12. Jung, Y.C., Hong, S.K. and Kim, S.Y.,

Crossref

13. Kwon, Y.G. and Kim, H.S., Color Studies Digest, Nalmada, 2011.

Crossref

14. Luther, J., University Investment in the Library: What's the return?, Paper presented in library connect seminar arranged by Elsevier in Québec, 2008.

Crossref

Google Scholar

15. Lee, Y.S., A Proposal on Ways of Arranging Books in Libraries through Color Management, Journal of Korea Design Knowledge, 28, 121-130, 2013.

Crossref

16. Lynch, S.N. and Mulero, E., Dewey? At this library with a very different outlook, they don't, New York Times, 2007 http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/14/us/14dewey.html (retrieved January 06, 2016)

Crossref

17. National Library Statistics System Home page, 2016 http://www.libsta.go.kr (retrieved January 06, 2016)

Crossref

18. Park, J.Y., A Study on the Operating Status and Development Direction of Public Library in Busan Metropolitan City, Journal of Korean Library and Information Science Society, 43(4), 69-88, 2012.

Crossref

Google Scholar

19. Park, K.Y., Song, S.H. and Kim, E.K.,

Crossref

20. Raymond, J., Librarians Have Little To Fear from Bookstores, Library Journal, 123(15), 41-42, 1998.

Crossref

Google Scholar

21. Satija, M.P., Colon Classification 7th edition: Some Perspectives. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Limited, 1993.

Crossref

22. Shapiro, S.S. and Wilk, M.B., An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika, 52(3-4), 591-611, 1965.

Crossref

Google Scholar

23. Thompson, J., The end of libraries. The Electronic Library, 1(4), 245-255, 1983. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb044603

Crossref

24. Yoo, J.O., A Study on Academic Library User's Information Literacy, Journal of the Korean Biblia Society for Library and Information Science, 15(2), 241-254, 2004.

Crossref

Google Scholar

25. Yoon, H.Y., Correlation analysis between national competitiveness and national research competitiveness in OECD Countries, Journal of the Korean Society for Library and Information Science, 41(1), 105-123, 2007.

Crossref

Google Scholar

PIDS App ServiceClick here!