eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Hyun Kyoon Lim

, Jooyeon Ko

10.5143/JESK.2018.37.6.733 Epub 2019 January 02

Abstract

Objective: This study examined the reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life (CP QOL) questionnaire.

Background: Quality of life (Qol) for the children with cerebral palsy (CP) is also essential aspect of the functioning. However, few Qol assessment tools specific to CP are available in South Korea.

Method: The English version of the Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life (CP-QOL) parent proxy form and the CP-child self-report form was translated into Korean. This study was to verify the reliability and validity of the two Korean versions of the CP-QOL documents. A total of 153 primary caregivers and 61 CP children answered the Korean questionnaires in two sessions two weeks apart. The reliability and validity were analyzed using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), Cronbach's α, and ANOVA.

Results: Cronbach's α ranged from 0.80 to 0.92 for the Korean version of the CP-QOL (K-CP-QOL) parent proxy form and from 0.84 to 0.96 for the child self-report form. All ICCs were above 0.75 except for emotional well-being and pain for the parent proxy form. For the K-CP-QOL child self-report form, all ICCs were 0.75 except for pain. There were significant differences in the feeling about function, emotional well-being, pain, and participation by the CP functional severity.

Conclusion: The K-CP-QOL parent proxy and child self-report forms appear to be valid to use for Korean CP children and their parents.

Application: Korean version of the CP-Qol could be used for both of clinical and research purposes.

Keywords

Cerebral palsy; Children; Reliability; Assessment; Quality of life

Cerebral Palsy (CP) is one of the most common childhood disorders, affecting about 2.5 out of every 1,000 new born babies. CP is caused by a non-progressive brain lesion during a baby's early developmental period (Oskoui et al., 2013). Preterm delivery (59.5%) and low birth weight (60.3%) were also the main causes of CP children in Korea (Yim et al., 2017). This non-progressive brain lesion can generate a permanent abnormal posture and movement disorder, including problems with sensation, perception, cognition, and communication (Rosenbaum et al., 2007a) Understanding the levels of the disability is critical for guiding intervention policies.(Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics et al., 2016). Because of those conditions, the quality of life of CP children is much affected by their limited ability to participate in normal activities (Rosenbaum et al., 2007b). For those reasons, it is important to assess the quality of life of CP children as well as their motor functions when their clinical outcomes are evaluated (Bjornson and McLaughlin, 2001; Viehweger et al., 2008). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines quality of life as "an individual's perception of their position in life, in the context of culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns" (Illum and Gradel, 2017; 1993).

There are two measurement tools to evaluate the quality of life for children: a generic measure and a condition-specific measure (Baars et al., 2005; Mueller-Godeffroy et al., 2016). The generic measurement tool is used to evaluate the quality of life of children whether or not they have a disease. It is, however, not an efficient tool to evaluate the intervention effect on children with specific conditions because the generic tool does not have the ability to evaluate a specific condition or a certain disability. The condition-specific tool, in contrast, is good for evaluating the difference before and after an intervention. It is also effective for evaluating small status changes of a patient over time (Bjornson and McLaughlin, 2001; Sakzewski et al., 2012).

A CP-specific measurement tool covers many aspects, including physical health, body pain and discomfort, daily living tasks, participation in regular physical and social activities, emotional well-being and self-esteem, interaction with the community, communication, family health, supportive physical environment, access to services, financial stability, and social well-being (Waters et al., 2005). The generic tool could not analyze those areas in detail and it reveals only the factors affecting the quality of life for the CP children (Waters et al., 2005).

The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) CP Module and the DISABKIDS CP Module were designed as condition-specific tools to measure the quality of life for CP children (Varni et al., 2006). However, they also began to show limitations in measuring quality of life in detail because they could not measure the feeling of the life with CP and they focus much on the caregivers. In the meantime, the Cerebral Palsy-Quality of Life (CP-QOL) questionnaire, a condition-specific quality of life assessment tool, was developed by a team of clinicians, scientists, parents/foster parents of CP children as well as children with mild to severe CP who communicated well. The CP-QOL provides two different forms: the primary caregiver proxy form and the child self-report form. The two forms have shown high validity and reliability (Waters et al., 2005).

Outcome measure research on CP children is also increasing in Korea. However, it is not easy to find a reliable quality of life assessment tool for the Korean CP children except one study on the path analysis of strength, spasticity, gross motor function and health-related QOL (Park, 2018). The original English version of the CP-QOL questionnaire has been translated and validated into several languages, including Turkish, Chinese, Brazilian, Portuguese, and Hindi (Wang et al., 2010; Braccialli et al., 2016; Das et al., 2017; Atasavun Uysal et al., 2016).

In this study, we translated and validated the original English version of the CP-QOL parent proxy form and the child self-report form into Korean. Specifically, the purposes of this study were to investigate the reliability of the Korean versions of the CP-QOL (K-CP-QOL) forms and to examine the construct validity by the CP severity and gender. It would be also a good example study for researchers studying the quality of life of the Korean seniors regarding their physical health, body pain and discomfort, daily living tasks and so on using a questionnaire to measure physical and social activities, emotional well-being and self-esteem.

2.1 Participants

We gathered data from five different rehabilitation centers in South Korea. Informed consent forms were obtained from the parents. There were two inclusion criteria: 1) CP children aged 9~12 who could understand and answer questionnaire questions or could otherwise self-report, and 2) parents with 4~12 year-old CP children who could complete the questionnaire. The exclusion criterion was CP children who might have been infected by the Botulinum Toxin, including an injection or any surgical surgery in 6 months before the study. A total of 61 children with cerebral palsy participated in the study (boys=39, girls=22, and average age=9.6± 1.6 years) for the child’s self-report. CP types were spastic (n=54), dyskinesia (n=3), and ataxia (n=4). A total of 153 parents participated in the study who had a CP child (boys=98, girls=55, and average age=7.1±2.4 years) for the parent proxy. Mainly the mothers (n=149, 97.4%, average age=38.6±2.0 years) completed the questionnaires. CP types of the children were spastic (n=54), dyskinesia (n=3), and ataxia (n=4).

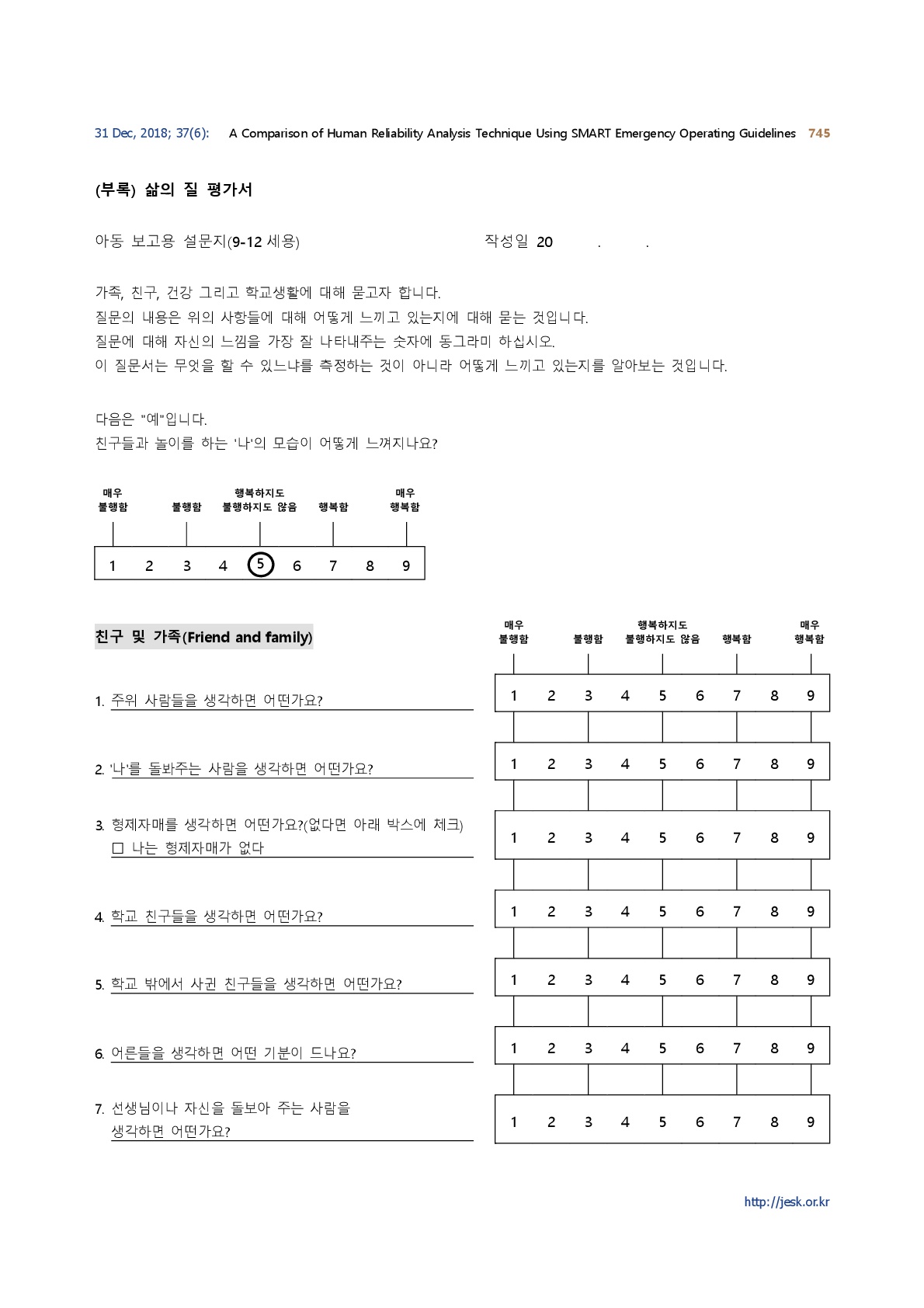

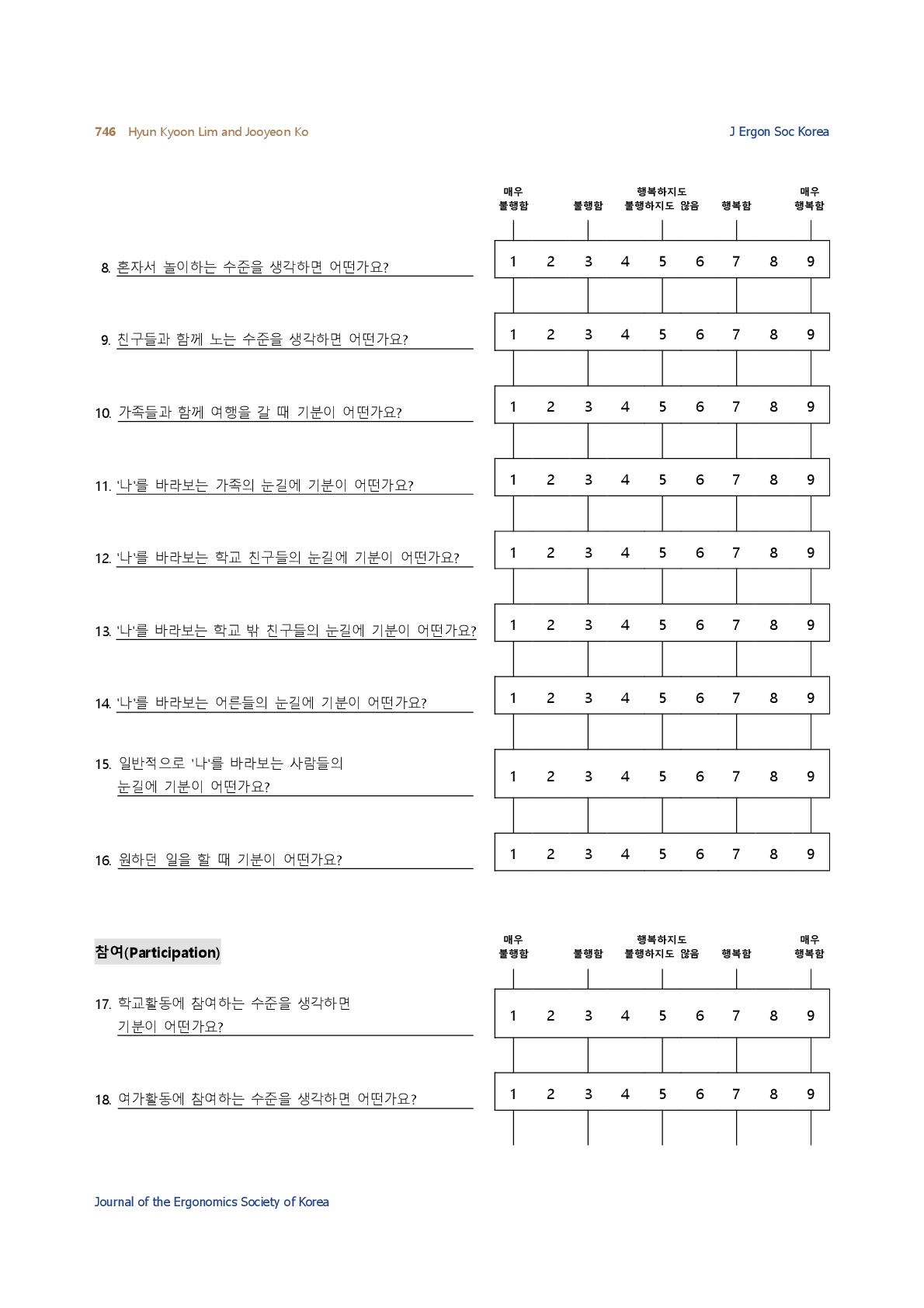

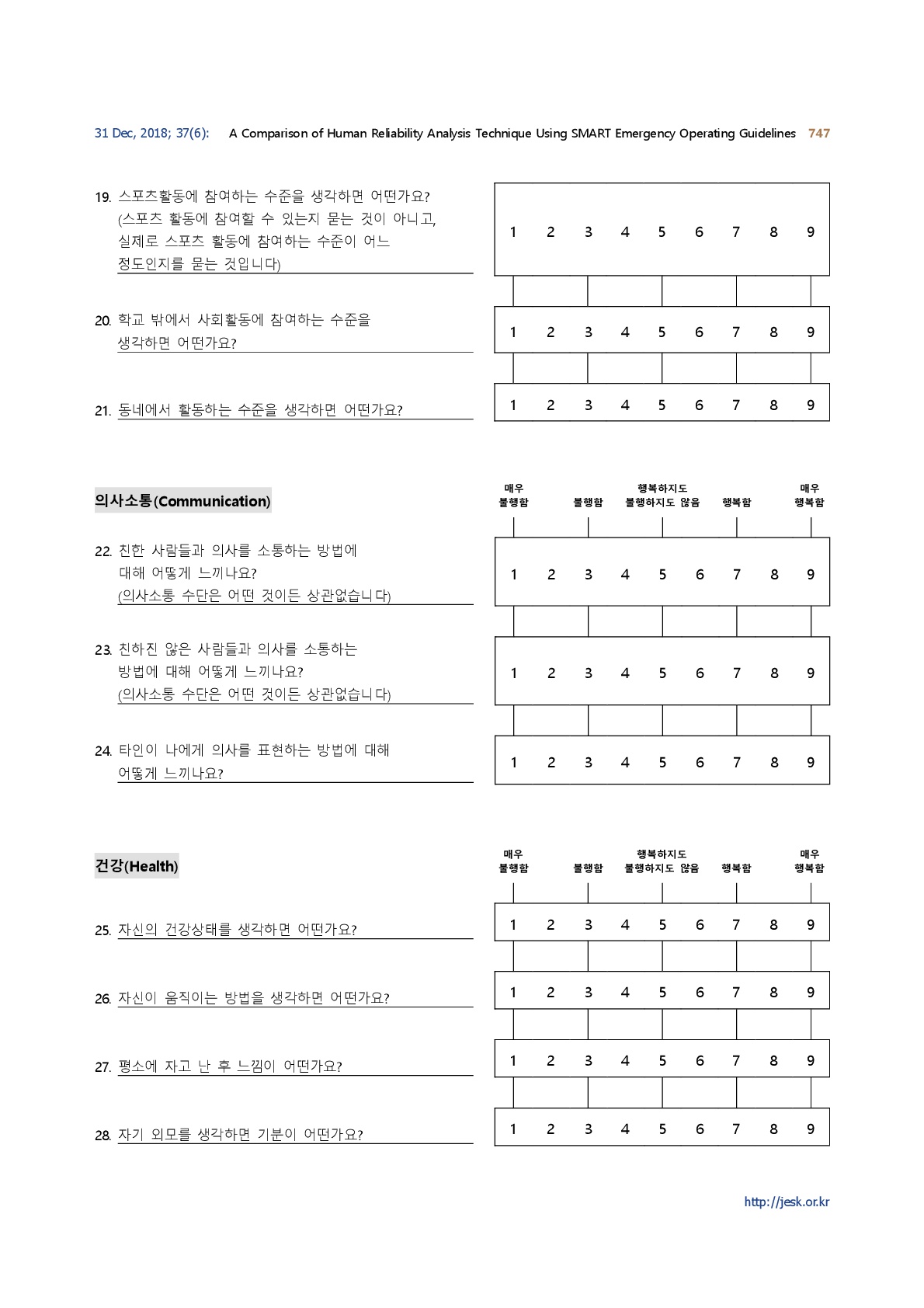

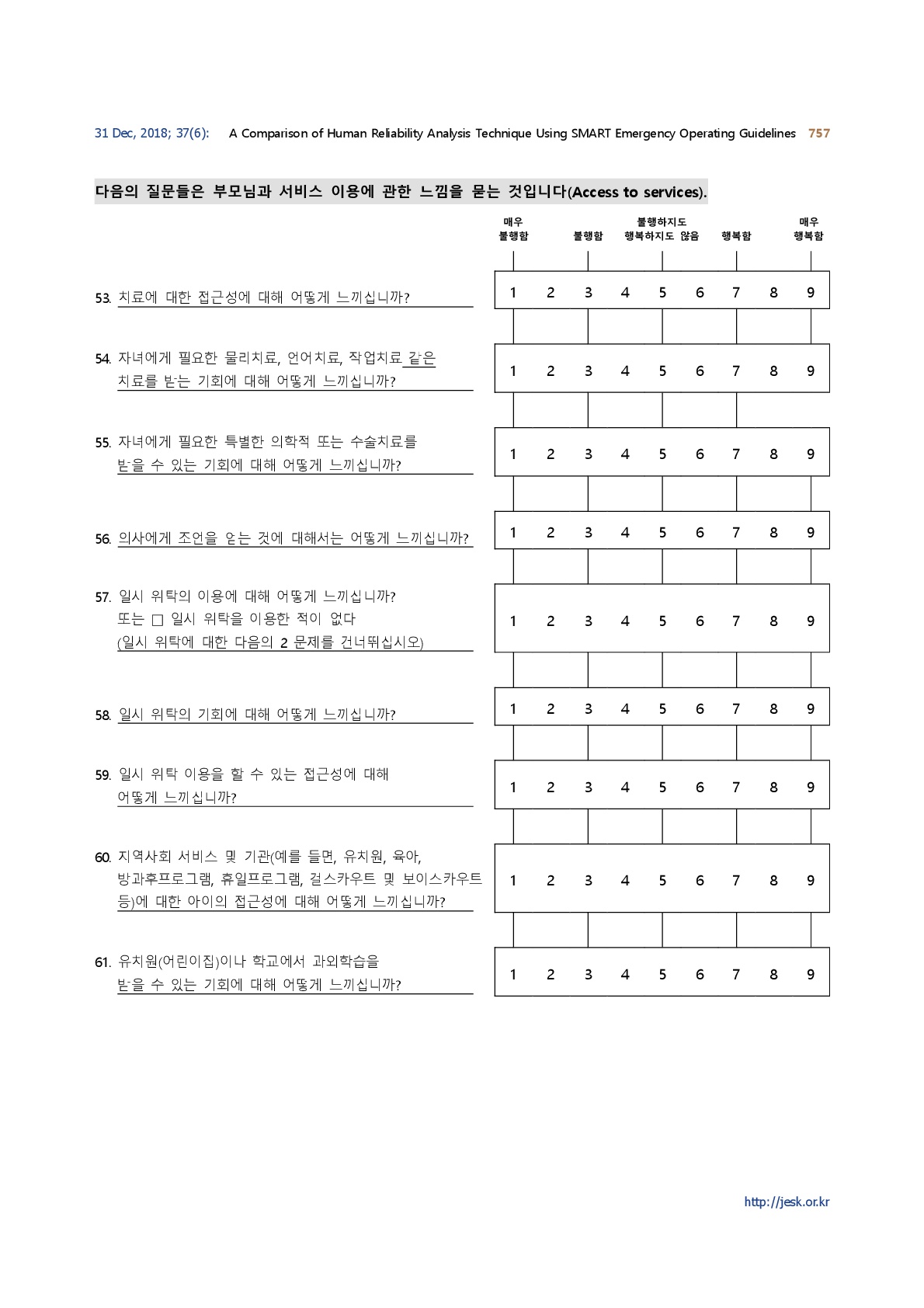

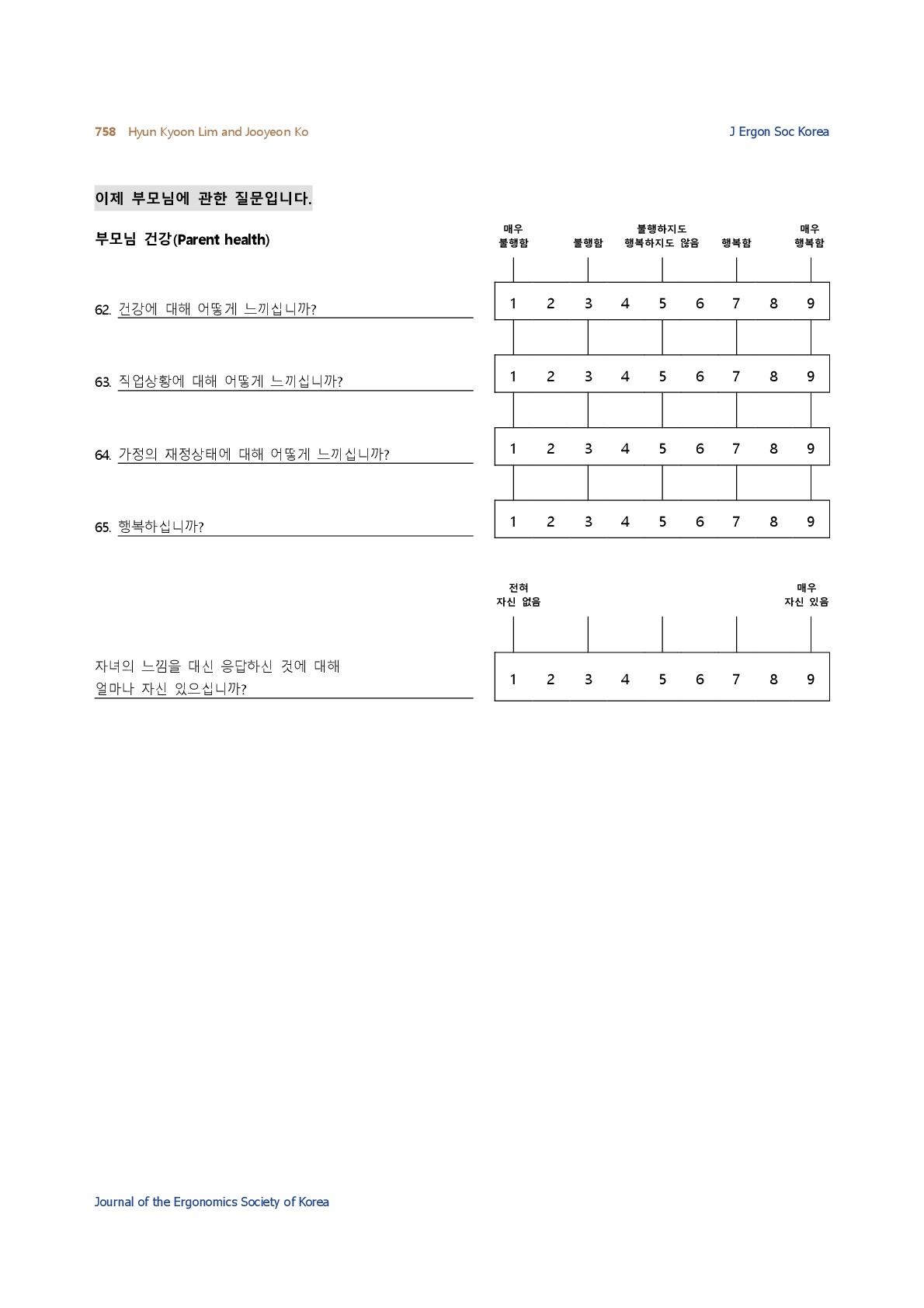

2.2 Cerebral Palsy-Quality of Life (CP-QOL) questionnaire

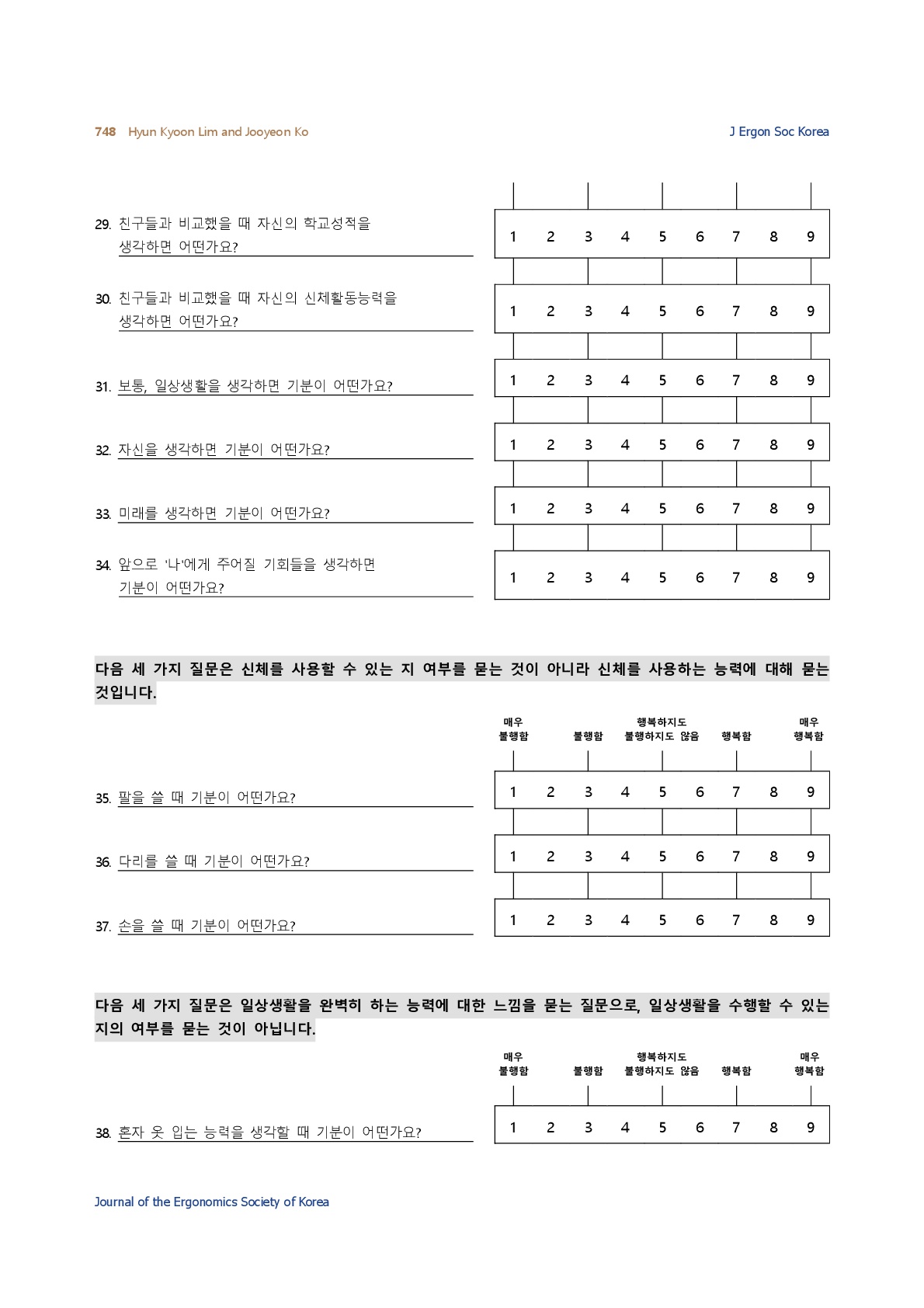

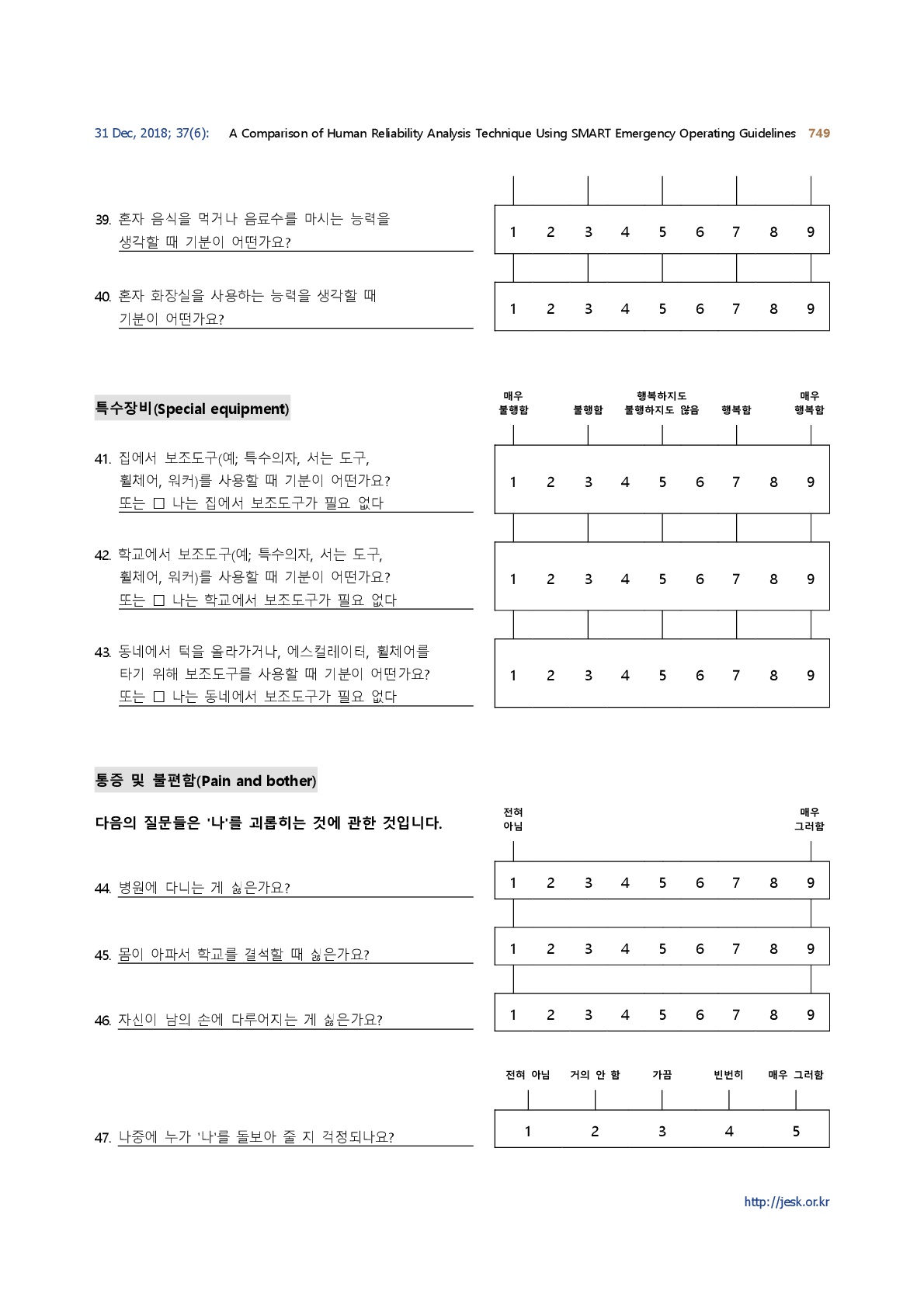

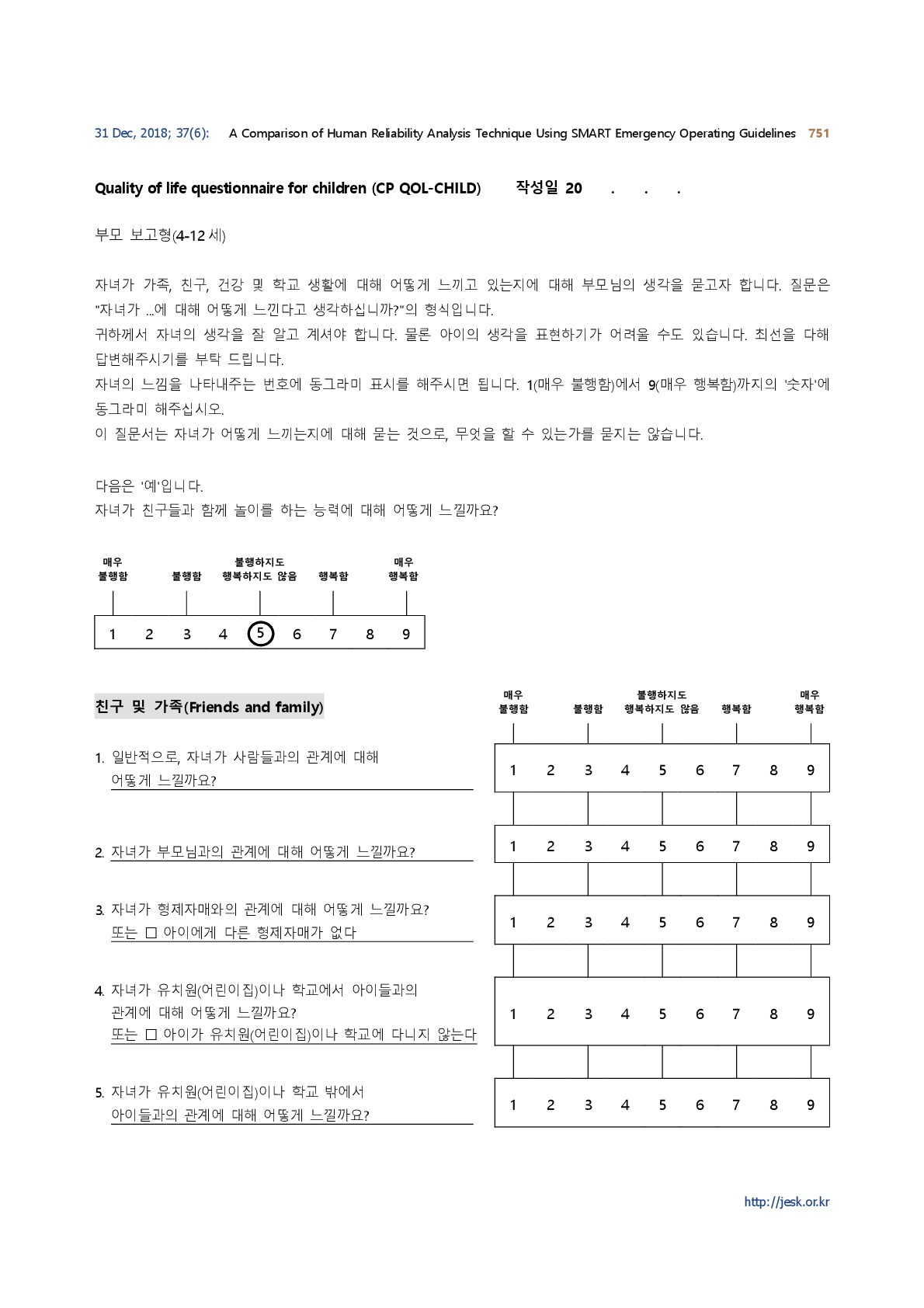

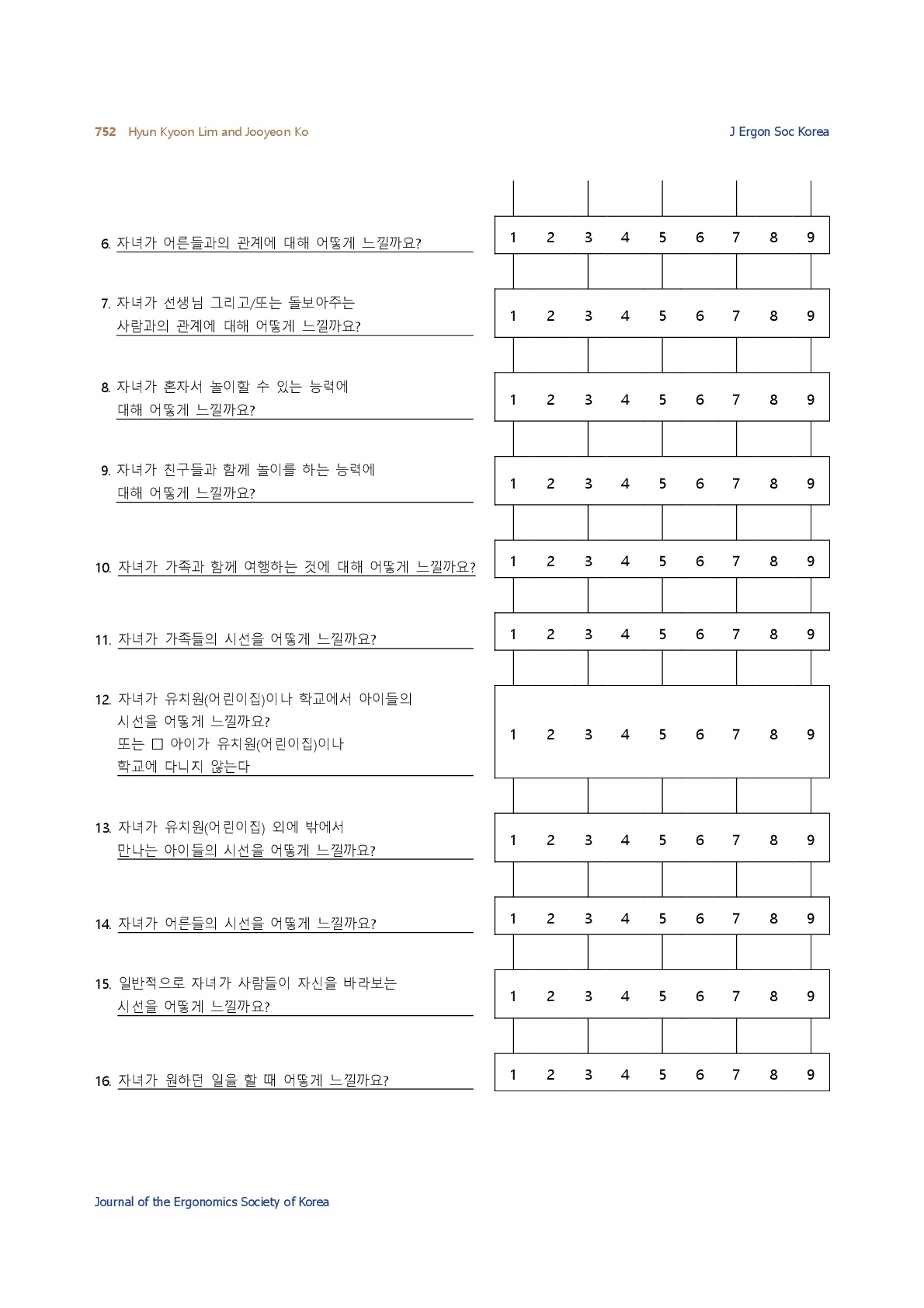

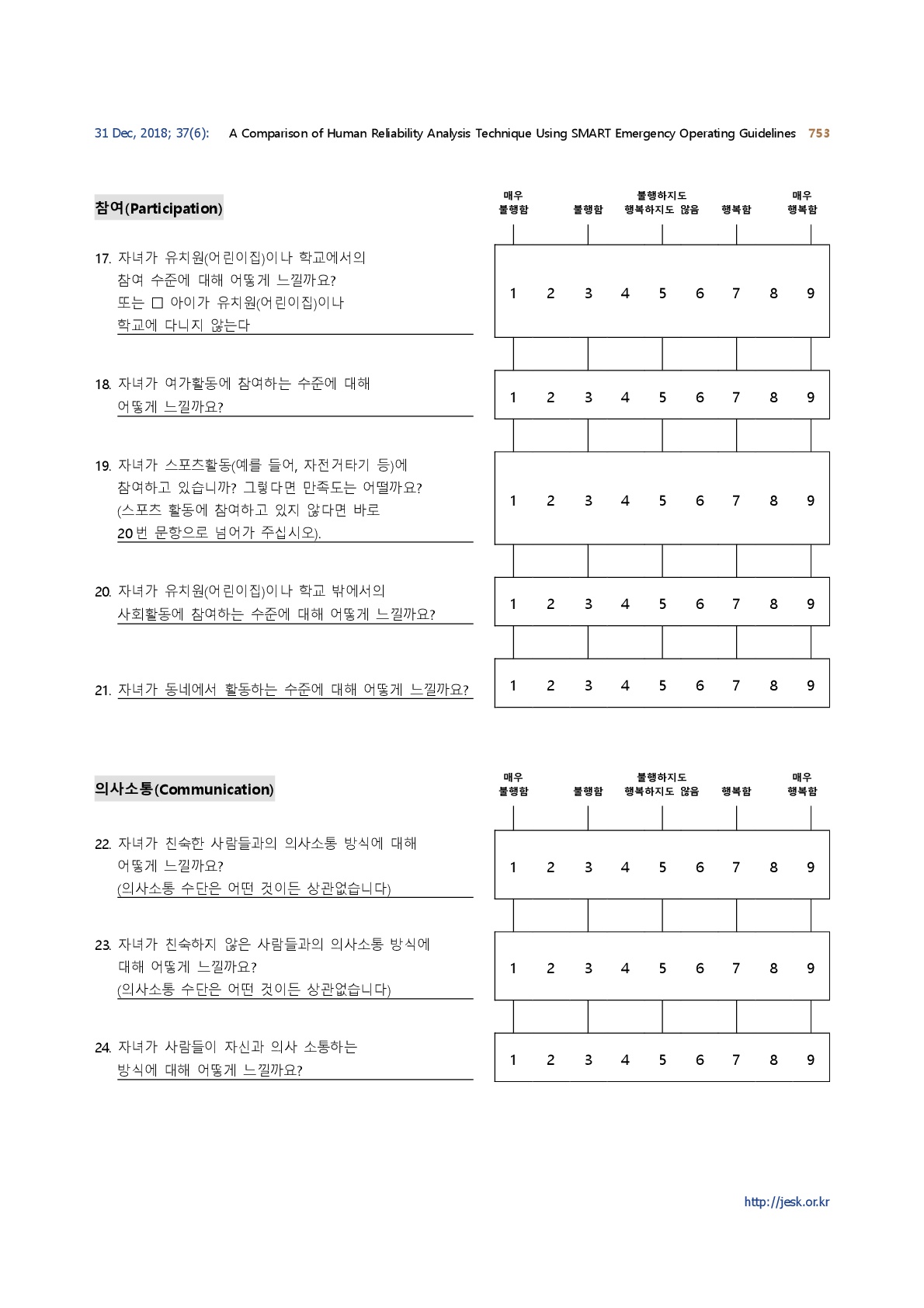

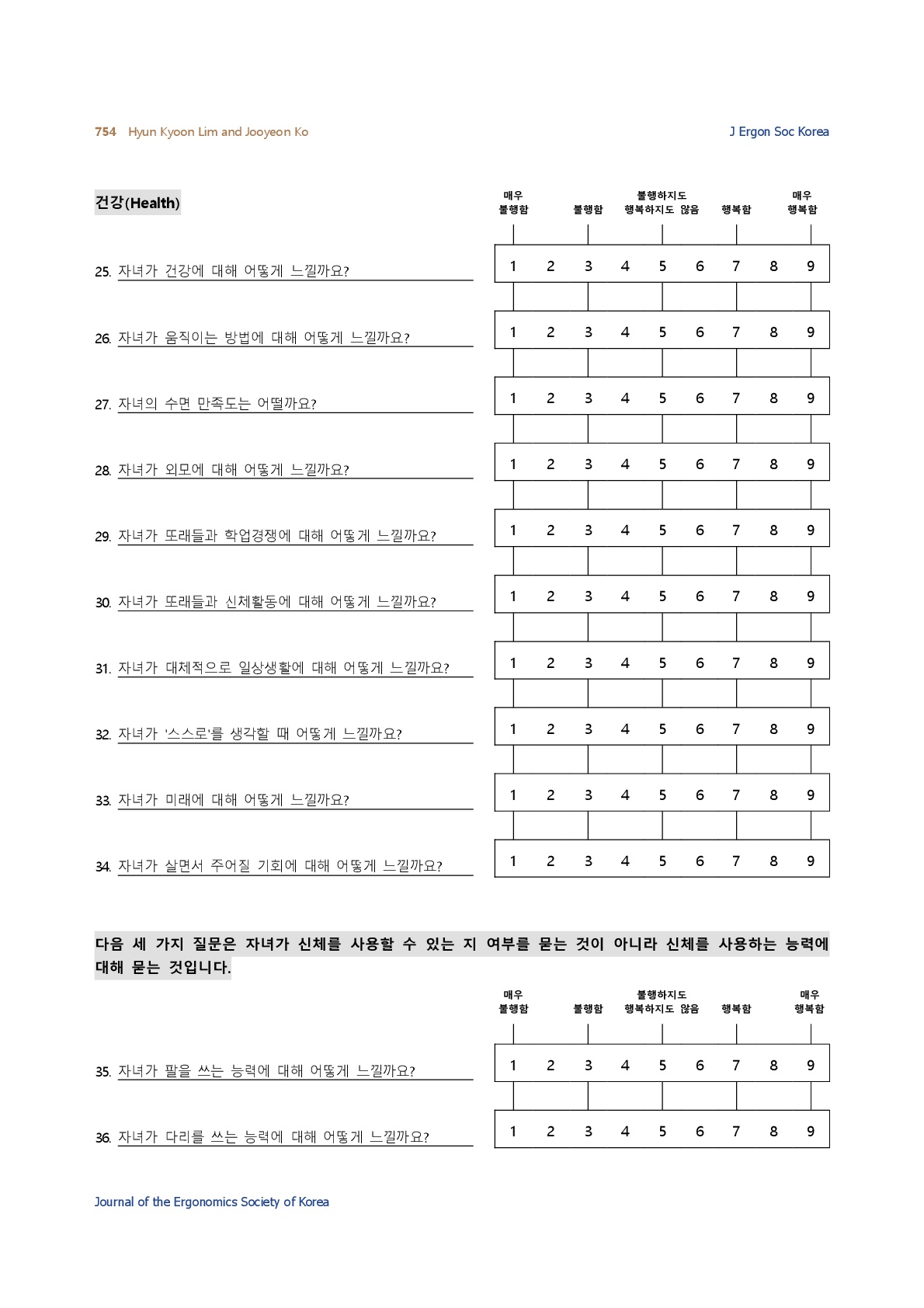

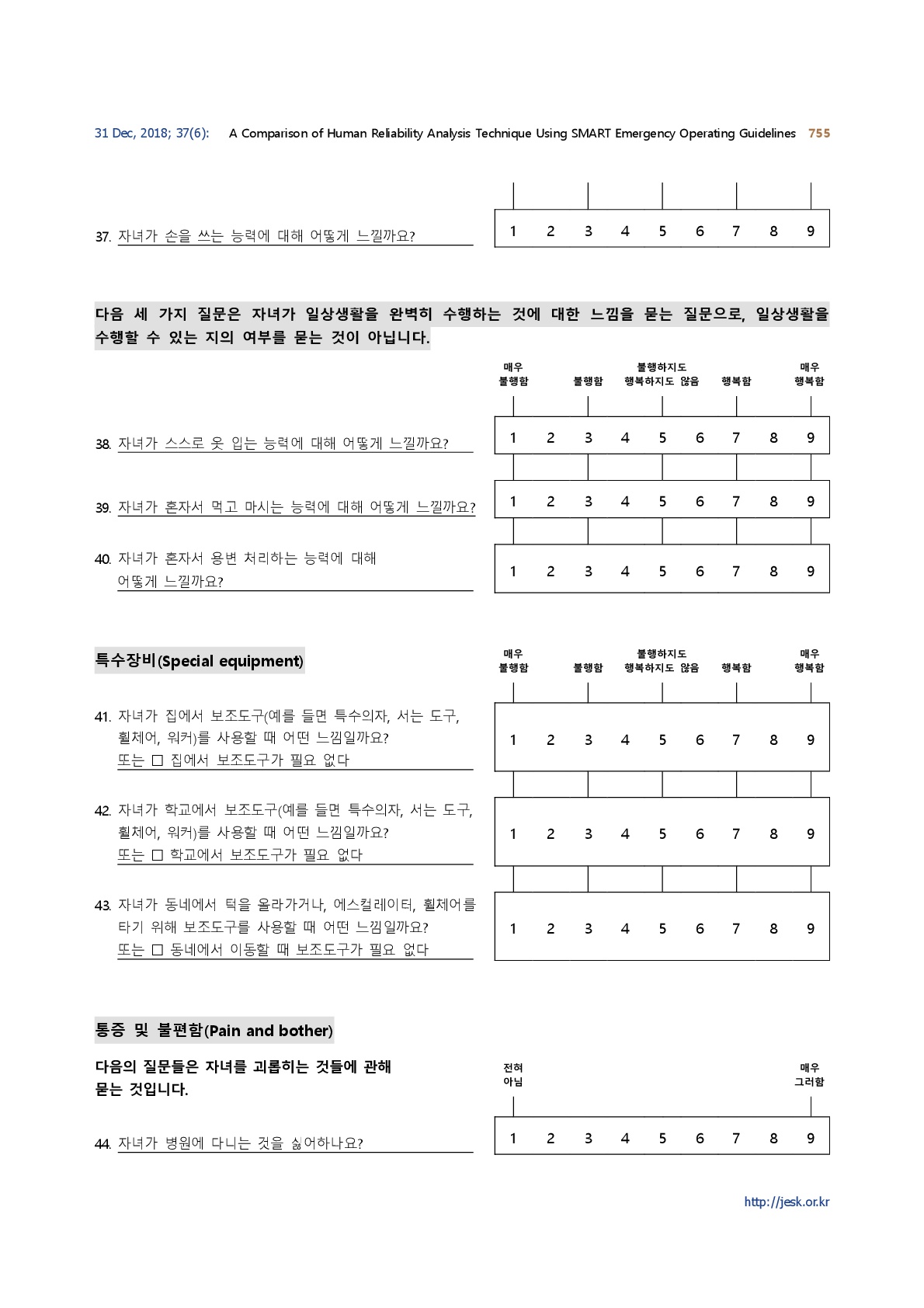

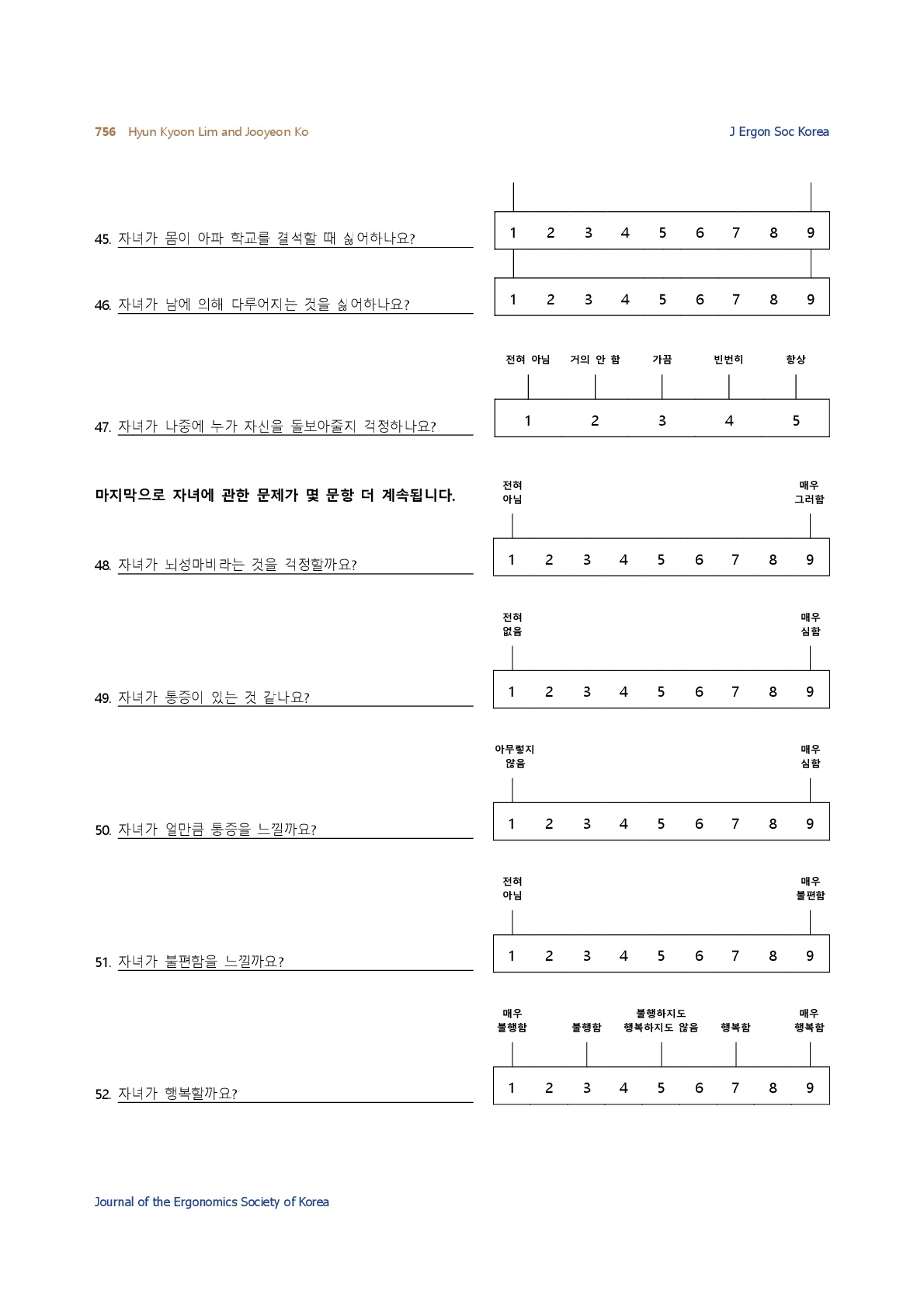

The CP-QOL questionnaires consisted of Cerebral Palsy-Quality of Life parent proxy (CP-QOL parent proxy) and Cerebral Palsy-Quality of Life child self-report (CP-QOL child self-report). The CP-QOL parent proxy had 66 questions for parents with CP children aged 4~12. CP-QOL child self-report had 52 questions for CP children aged 9~12 and it was for a direct report from the CP child. The CP-QOL parent proxy had questions to evaluate 7 domains: social well-being and acceptance, participation and physical health, functioning, emotional well-being, access to services, pain and impact of disability, and family health. The CP-QOL child self-report had the same domains except for access to services and pain and impact of disability. From 1 to 9 points was given to all questions except the 47th question (domain for pain and impact of disability); from 1 to 5 points was given to this question. These original scores were transformed to scaled score 0~100 points during the post process according to the manual; Questionnaire has both of positive and negative questions and therefore it needs the post process.

Higher scores indicate a better quality of life (Waters et al., 2007). Parents completed the CP-QOL parent proxy form and the CP-child completed the CP-QOL child self-report form. CP children were allowed to be assisted by a researcher or parents if they needed assistance with reading the questions or answering the questions. The CP-QOL questionnaire was completed either by face to face interviews or through the mail (Waters et al., 2007).

2.3 Functioning evaluation

For the essential features of the children, irrespective of having a motor disability, functional mobility and functional communication ability of the CP children were examined with the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) and the communication function classification system (CFCS).

The GMFCS-E & R is a classification method to differentiate the independence ability of CP children for their mobility from level I (walks without limitations) to the level V (transported in a manual wheelchair) (Palisano et al., 1997), which is a classification method used worldwide for CP children based on self-initiated movements such as sitting, transfers, and mobility (Begnoche et al., 2016). In this study, we used K-GMFCS-E & R written in Korean (Ko et al., 2011). In summary, according to the K-GMFCS, 13 (21%) children were level I, 26 (43%) level II, 10 (16%) level III, 8 (13%) level IV, and 4 (7%) level V for the child self-report. In addition, 23 (15%) children were level I, 39 (25%) level II, 25 (16%) level III, 42 (27%) level IV, and 24 (16%) level V for the parent proxy report.

The CFCS was developed in 2011 to evaluate the communication ability of CP children (Hidecker et al., 2011). The CFCS has five levels according to the ability of communication: from effective sender and receiver with unfamiliar and familiar partners (level 1) to seldom effective sender and receiver with familiar partners (level 5).

2.4 Questionnaire on demographic variables

Parents completed a questionnaire providing information about their employment, educational level, marital status, number of siblings, address, their child’s school grade, and which school they attended.

2.5 Translation and adaptation

We translated the English versions of the CP-QOL parent proxy form and the CP-QOL child self-report form into Korean. A forward translation, item reconciliation, backward translation, review of forward and backward translation, and pre-test cognitive interview were made sequentially with the permission of the original authors.

2.6 Statistical analysis for validation and reliability

To determine the reliability and validity of the CP-QOL parent proxy form and the CP-QOL child self-report form translated into Korean, parents and CP children answered the questionnaire twice with a two-week interval. Two research assistants helped them complete the questionnaires. A descriptive statistical analysis including average and standard deviations was made for continuous parameters. Frequency was analyzed for nominal parameters. Internal consistency was tested using Cronbach's α test. Test-retest reliability was determined using intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis. The ICC is generally considered excellent when the ICC ≥ 0.75; satisfactory when the 0.4 ≤ ICC < 0.75 and weak when the ICC < 0.4 (Hulley et al., 2013). The construct validity was evaluated using a t-test and a post hoc test in ANOVA for gender difference and GMFCS levels. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 18.0. A significance level of p<0.05 was used.

The general characteristics of the participants are listed in Table 1. The mean scores and standard deviations (SD) for each domain at baseline and follow-up (two weeks later from baseline) are presented in Table 2. From the K-CP-QOL parent proxy form, the highest domain score was 68.6, which was found in the domain of emotional well-being. From the K-CP-QOL child self-report form, the highest domain score 70.4, which was in the emotional well-being range. The lowest score was found in the domain of pain and feeling about disability for both the parent proxy (52.3) and child self-report forms (51.1). The results from the baseline and follow-up showed almost the same results.

|

CP-QOL parent proxy (N=153) |

CP-QOL child self-report

(N=61) |

|

|

Children's age

(years) |

7.1 ± 2.4 |

9.6 ± 0.6 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Boys |

98 (64.1) |

39 (63.9) |

|

Girls |

55 (35.9) |

22 (36.1) |

|

GMFCS |

|

|

|

I |

23 (15.0) |

13 (21.3) |

|

II |

39 (25.5) |

26 (42.6) |

|

III |

25 (16.3) |

10 (16.4) |

|

IV |

42 (27.5) |

8 (13.1) |

|

V |

24 (15.7) |

4 (6.6) |

|

CFCS |

|

|

|

I |

70 (45.8) |

48 (78.7) |

|

II |

29 (19.0) |

12 (19.7) |

|

III |

29 (19.0) |

1 (1.6) |

|

IV |

12 (7.8) |

- |

|

V |

13 (8.4) |

- |

|

CP types |

|

|

|

Spastic |

125 (81.7) |

54 (88.5) |

|

Dyskinesia |

13 (8.5) |

3 (4.9) |

|

Hypotonia |

8 (5.2) |

4 (6.6) |

|

Ataxia |

4 (2.6) |

- |

|

Mixed |

3 (2.0) |

- |

|

Visual impairment |

|

|

|

Yes |

26 (17.0) |

2 (3.3) |

|

No |

127 (83.0) |

59 (96.7) |

|

School grade |

|

|

|

Preschooler |

92 (60.1) |

3 (4.9) |

|

Elementary 1 |

18 (11.8) |

8 (13.1) |

|

Elementary 2 |

13 (8.5) |

6 (9.8) |

|

Elementary 3 |

11 (7.2) |

10 (16.4) |

|

Elementary 4 |

9 (5.9) |

12 (19.7) |

|

Elementary 5 |

5 (3.3) |

12 (19.7) |

|

Elementary 6 |

5 (3.3) |

10 (16.4) |

|

Type of schooling |

|

|

|

Kindergarten |

90 (58.8) |

3 (4.9) |

|

Special education school |

21 (13.7) |

16 (26.2) |

|

Mainstream school |

24 (15.7) |

35 (57.4) |

|

Special class in mainstream school |

13 (8.5) |

7 (11.5) |

|

Home schooling |

5 (3.3) |

- |

|

Mother's age (years) |

38.6 ± 4.0 |

|

|

Father's age (years) |

38.7 ± 1.2 |

|

|

Address |

|

|

|

Rural |

47 (30.7) |

|

|

City |

106 (69.3) |

|

|

Mother's

education levels |

|

|

|

High school |

63 (41.2) |

|

|

Junior college |

28 (18.3) |

|

|

Higher than university |

62 (40.5) |

|

|

Father's

education levels |

|

|

|

High school |

51 (33.3) |

|

|

Junior college |

21 (13.7) |

|

|

Higher than university |

81 (52.9) |

|

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

Married |

149 (97.4) |

|

|

Divorced |

4 (2.6) |

|

|

Father's job |

|

|

|

Yes |

146 (95.4) |

|

|

No |

7 (4.6) |

|

|

Mother's job |

|

|

|

Yes |

17 (11.1) |

|

|

No |

136 (88.9) |

|

|

Siblings |

|

|

|

None |

25 (16.3) |

|

|

More than one |

128 (83.7) |

|

|

Respondent |

|

|

|

Mother |

149 (97.4) |

|

|

Father |

4 (2.6) |

|

|

|

Baseline |

Follow-up |

||

|

Mean (SD) |

Min-Max |

Mean (SD) |

Min-Max |

|

|

CP-QOL parent proxy |

|

|

|

|

|

Social well-being and

acceptance |

66.2 (9.9) |

38.8~91.6 |

64.8 (9.9) |

38.9~92.7 |

|

Feelings about functioning |

57.9 (13.1) |

13.5~86.5 |

55.5 (14.3) |

10.4~97.9 |

|

Participation and physical

health |

57.6 (13.1) |

14.8~87.5 |

55.5 (13.8) |

18.1~89.8 |

|

CP-QOL

parent proxy |

|

|

|

|

|

Emotional well-being |

68.6 (11.5) |

35.4~97.9 |

63.4 (12.9) |

27.1~100 |

|

Access to services |

56.2 (14.4) |

13.5~89.6 |

55.7 (15.9) |

13.5~93.5 |

|

Pain and feeling about disability |

52.3 (13.4) |

12.5~88.6 |

51.8 (14.5) |

0~88.6 |

|

Family health |

55.3 (15.8) |

18.8~93.8 |

54.9 (16.6) |

21.9~93.8 |

|

CP-QOL

child self-report |

|

|

|

|

|

Social well-being and acceptance |

64.0 (14.1) |

28.1~100.0 |

66.4 (14.1) |

33.3~100.0 |

|

Feelings about functioning |

63.6 (12.2) |

33.3~91.7 |

66.1 (13.5) |

31.3~94.8 |

|

Participation and physical health |

65.0 (14.8) |

26.1~95.5 |

66.5 (14.2) |

27.3~97.7 |

|

Emotional well-being |

68.8 (17.3) |

31.3~100.0 |

70.4 (15.7) |

37.5~100.0 |

|

Pain and feeling about disability |

51. 1(13.6) |

22.8~77.7 |

50.3 (14.0) |

19.7~90.6 |

To examine reliability for the K-CP-QOL, internal consistency and test-retest reliability were obtained. Cronbach's α ranged from 0.80 to 0.92 for the parent proxy form and from 0.84 to 0.96 for the child self-report form (Table 3), which indicates good to excellent internal consistency. All ICCs were above 0.75 except for the emotional well-being (ICC=0.73) and pain and feeling about disability (ICC=0.67) for the K-CP-QOL parent proxy form. For the child self-report, all ICCs were 0.75 except for the pain and feeling about disability (ICC=0.72).

|

CP-QOL |

Internal consistency |

Test-retest reliability |

||||

|

Parent proxy |

Child self-report |

Parent proxy |

Child self-report |

|||

|

Cronbach's α |

Cronbach's α |

ICC |

95% CI |

ICC |

95% CI |

|

|

SWB |

0.87 |

0.96 |

0.76 |

0.69~0.82 |

0.93 |

0.88~0.96 |

|

FUN |

0.90 |

0.94 |

0.82 |

0.76~0.87 |

0.88 |

0.81~0.93 |

|

PART |

0.90 |

0.91 |

0.82 |

0.76~0.87 |

0.83 |

0.73~0.89 |

|

EWB |

0.85 |

0.90 |

0.73 |

0.65~0.80 |

0.83 |

0.72~0.89 |

|

ACCESS |

0.90 |

- |

0.82 |

0.76~0.87 |

- |

- |

|

PAIN |

0.80 |

0.84 |

0.67 |

0.57~0.75 |

0.72 |

0.57~0.82 |

|

FAMILY |

0.92 |

- |

0.85 |

0.81~0.89 |

- |

- |

To investigate the construct validity for the K-CP-QOL, the mean and SD by the GMFCS levels and sex were obtained. For the parent proxy version, statistically significant differences were found between the child’s functional level and in areas such as feelings about functioning (p=0.034), emotional well-being (p=0.015), and pain and feeling about disability (p=0.037) (Table 4). For child-report version, a significant different was found between participation and physical health (p=0.039). There was no statistically significant gender difference between girls and boys in either questionnaire (Table 4).

|

CP-QOL |

Level of GMFCS |

Sex |

|||||||

|

Parent proxy |

I (n=23) |

II (n=39) |

III (n=25) |

IV (n=42) |

V (n=24) |

|

Boy |

Girl |

|

|

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

p |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

p |

|

|

SWB |

62.0 (11.6) |

67.6 (8.3) |

66.2 (9.0) |

66.5 (10.0) |

66.9 (10.6) |

0.276 |

65.9 (8.64) |

66.5 (11.7) |

0.71 |

|

FUN* |

51.6 (16.5) |

58.1 (12.2) |

56.7 (9.7) |

58.2 (14.5) |

63.7 (8.5) |

0.034 |

57.6 (12.7) |

58.1 (13.8) |

0.81 |

|

PART |

52.3 (14.6) |

57.3 (11.0) |

56.8 (9.7) |

58.5 (14.6) |

62.4 (13.4) |

0.114 |

57.7 (12.2) |

57.5 (14.4) |

0.95 |

|

EWB* |

61.7 (13.2) |

70.6 (8.9) |

67.7 (10.3) |

68.7 (12.5) |

72.3 (10.9) |

0.015 |

68.2 (11.2) |

69.2 (12.1) |

0.60 |

|

ACCESS |

53.2 (16.3) |

57.2 (13.4) |

56.3 (14.1) |

55.8 (15.3) |

57.6 (13.5) |

0.845 |

56.1 (13.3) |

56.3 (16.3) |

0.95 |

|

PAIN* |

48.6 (12.9) |

54.7 (9.9) |

54.3 (14.6) |

48.2 (12.7) |

56.7 (16.4) |

0.037 |

52.6 (13.9) |

51.6 (12.3) |

0.65 |

|

FAMILY |

48.5 (12.6) |

59.6 (15.0) |

51.5 (19.9) |

57.2 (13.9) |

55.4 (16.0) |

0.052 |

54.3 (14.6) |

57.1 (17.5) |

0.31 |

|

Child self -report |

I (n=13) |

II (n=26) |

III (n=10) |

IV (n=8) |

V (n=4) |

|

Boy |

Girl |

|

|

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

p |

Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) |

p |

|

|

SEB |

65.2 (16.5) |

62.4 (10.6) |

66.9 (16.4) |

66.4 (15.5) |

58.5 (21.7) |

0.811 |

63.2 (14.3) |

65.5 (14.0) |

0.54 |

|

FUN |

66.9 (15.4) |

62.9 (10.1) |

66.3 (10.6) |

64.1 (12.2) |

49.7 (11.3) |

0.148 |

63.7 (10.7) |

63.3 (14.7) |

0.91 |

|

PART* |

73.5 (16.2) |

64.0 (13.0) |

66.8 (14.2) |

59.8 (11.6) |

49.7 (17.5) |

0.039 |

64.8 (14.4) |

65.3 (15.8) |

0.89 |

|

EWB |

74.6 (15.7) |

66.9 (17.9) |

75 (12.9) |

65.6 (19.6) |

53.1 (17.1) |

0.157 |

67.6 (17.4) |

70.9 (17.4) |

0.48 |

|

PAIN |

53.3 (12.2) |

47.4 (13.6) |

54.0 (10.6) |

55.2 (15.3) |

51.9 (22.4) |

0.505 |

53.1 (13.9) |

47.5 (12.7) |

0.12 |

It is necessary and important to effectively measure the quality of life of children with CP to make a better strategies for better outcomes (Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics et al., 2016). Psychometric properties of the CP-QOL have been primarily suggested and measured by a standardized method that was translated into many languages, including Polish, Chinese, Brazilian, and Turkish from the English version (Wang et al., 2010; Braccialli et al., 2016; Atasavun Uysal et al., 2016; Waters et al., 2007; Dmitruk et al., 2014).

Physical function and psychometric properties are highly related and should be measured precisely to provide appropriate information on them (Chae et al., 2018). This study was designed to verify and evaluate whether the psychometric properties of both the CP-QOL parent proxy and CP-QOL child-report forms translated into Korean were acceptable. Sometimes cultural difference confuses people and makes it difficult for them to understand a sentence if they do not have enough background knowledge or if they are from multiple cultural environments (Braccialli et al., 2016). No additional cultural adaptation, however, was necessary during this study. No parents or children reported such problems.

Internal consistency (= Cronbach's α) from the previous studies was 0.74~0.92 for the CP-QOL parent proxy form, 0.80~0.90 for the CP-QOL child self-report (English version, (Waters et al., 2007), 0.78~0.91 for the parent proxy form, 0.84~0.89 for the child self-report (Chinese version, (Wang et al., 2010)), and 0.63~0.93 for the parent proxy form, 0.61~0.92 for the child self-report (Atasavun Uysal et al., 2016). Internal consistency analysis of the K-CP-QOL was 0.80~0.92 for the CP-QOL parent proxy form, 0.84~0.96 for the CP-QOL child self-report which showed similar internal consistency or slightly stronger internal consistency compared to other language versions. In our best understanding, the judgement of parents on their children's function are more sensitive than the judgement of children because the parents, especially mothers, are much emotionally changeable to their child's functions. It might be the reason why ICC values of parent-proxy were lower than those of child self-report.

For the test-retest reliability, ICCs were reported for the parent-proxy form in English, Chinese, Brazilian-Portuguese, and Turkish. The ICCs ranged from 0.76 to 0.89 for the English version (N=205), from 0.86 to 0.97 for the Chinese version (N=145), from 0.62 to 0.81 for the Brazilian-Portuguese (N=30), and from 0.82 to 0.97 for the Turkish version (N=149). This study (N=153) showed 0.67 to 0.85, which were similar or slightly greater ICC values than the Chinese version. Compared to countries such as Brazil, Portugal, and Turkey, the ICC values of this study were not higher.

ICCs of CP-QOL child-report forms have been reported for Chinese, Brazilian, and Turkish version. The ICCs ranged from 0.74 to 0.92 for the Chinese version (N=44), 0.41~0.89 for the Brazilian (N=65), and 0.91~0.97 for the Turkish version (N=58). In the Korean version, the ICCs were 0.72~0.93 (N=61). The reliability of the Korean version had a level similar to those of other countries' language versions.

Quality of life is an important aspect for CP children. In general, the quality of life of CP children is related to gender and the physical functional level as well as the parental psychological status (Bult et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2012). It has been suggested that the parent's psychological state should also be measured when the parent proxy is used to evaluate the status of CP children because they are somehow related (Davis et al., 2012). In this study, the structural validity was evaluated by the methods proposed by the Polish and Turkish versions of the CP-QOL. Some significant differences were found between groups classified by the GMFCS levels. However, we did not find any significant differences between genders.

This study methods using a questionnaire to analyze the quality of life of the CP children and their parents could be also applied to the senior people because their disabled functions and discomfort are the exactly the same to the disabled people (Cho et al., 2018). It would be also applied to the geriatric patients with cancer (Won et al., 2018), stroke (Yang et al., 2017), or diabetes (Kim and Kim, 2017) to measure their quality of life.

A limitation of this study is that we did not measure the parent's psychological status. It should be considered in future studies. In addition, the total number of CP children (N=61) that participated in this study for the CP-QOL child-report form was relatively small. Even though it was neither the smallest number of CP children nor the greatest compared to previous studies, in the English version (N=53) Chinese version (N=44), or Brazilian-Portuguese (N=65), the sampling number was still not great enough. It was not easy to recruit children between 9 and 12 years-old. Furthermore, it would be valuable to examine changes in the quality of life for the CP children using K-CP-QOL questionnaires from the longitudinal intervention.

We conducted a study to determine the psychometric properties of the Korean version of the CP-QOL questionnaires. The results showed high consistency and reliability for the Korean version for measuring the quality of life of CP children. Thus, it is a suitable and reliable assessment tool to evaluate Korean CP children's quality of life.

References

1. Atasavun Uysal, S., Duger, T., Elbasan, B., Karabulut, E. and Toylan, I., Reliability and Validity of The Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire in The Turkish Population, Perceptual and Motor Skills, 122(1), 150-164, 2016.

Crossref

Google Scholar

2. Baars, R.M., Atherton, C.I., Koopman, H.M., Bullinger, M., Power, M. and Group, D., The European DISABKIDS project: development of seven condition-specific modules to measure health related quality of life in children and adolescents, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 3, 70, 2005.

Crossref

Google Scholar

3. Begnoche, D.M., Chiarello, L.A., Palisano, R.J., Gracely, E.J., Mccoy, S.W. and Orlin, M.N., Predictors of Independent Walking in Young Children With Cerebral Palsy, Physical Therapy, 96(2), 183-192, 2016.

Crossref

Google Scholar

4. Bjornson, K.F. and McLaughlin, J.F., The measurement of health-related quality of life (HRQL) in children with cerebral palsy, European Journal of Neurology, 8 Suppl 5, 183-193, 2001.

Crossref

Google Scholar

5. Braccialli, L.M., Almeida, V.S., Sankako, A.N., Silva, M.Z., Braccialli, A.C., Carvalho, S.M. and Magalhães, A.T., Translation and validation of the Brazilian version of the Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children - child report, Journal de Pediatria, 92(2), 143-148, 2016.

Crossref

Google Scholar

6. Bult, M.K., Verschuren, O., Jongmans, M.J., Lindeman, E. and Ketelaar, M., What influences participation in leisure activities of children and youth with physical disabilities? A systematic review, Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(5), 1521-1529, 2011.

Crossref

Google Scholar

7. Chae, S., Park, E.Y. and Choi, Y.I., The psychometric properties of the Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (CHAQ) in children with cerebral palsy, BMC Neurology, 18(1), 151, 2018.

Crossref

Google Scholar

8. Cho, H.J., Hong, T.H. and Kim, M., Physical and nutrition statuses of geriatric patients after trauma-related hospitalization: Data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013-2015, Medicine (Baltimore), 97(9), e0034, 2018.

Crossref

Google Scholar

9. Das, S., Aggarwal, A., Roy, S. and Kumar, P., Quality of Life in Indian Children with Cerebral Palsy Using Cerebral Palsy-quality of Life Questionnaire, Journal of Pediatric Neuroscience, 12(3), 251-254, 2017.

Crossref

Google Scholar

10. Davis, E., Mackinnon, A. and Waters, E., Parent proxy-reported quality of life for children with cerebral palsy: is it related to parental psychosocial distress?, Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(4), 553-560, 2012.

Crossref

Google Scholar

11. Dmitruk, E., Mirska, A., Kulak, W., Kalinowska, A.K., Okulczyk, K. and Wojtkowski, J., Psychometric properties and validation of the Polish CP QOL-Child questionnaire: a pilot study, Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(4), 878-884, 2014.

Crossref

Google Scholar

12. Global Burden of Disease Pediatrics Collaboration, Kyu, H.H., Pinho, C., Wagner, J.A. and Brown, J.C., Global and National Burden of Diseases and Injuries Among Children and Adolescents Between 1990 and 2013: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease 2013 Study, JAMA Pediatrics, 170(3), 267-287, 2016.

Crossref

Google Scholar

13. Hidecker, M.J., Paneth, N., Rosenbaum, P.L., Kent, R.D., Lillie, J., Eulenberg, J.B, Chester JR, K., Johnson, B., Michalsen, L., Evatt, M. and Taylor, K., Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 53(8), 704-710, 2011.

Crossref

Google Scholar

14. Hulley, S.B., Cummings, S.R., Browner, W.S., Grady, D., Hearst, N. and Newman, T.B., Designing Clinical Research, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2013.

Crossref

15. Illum, N.O. and Gradel, K.O., Parents' Assessments of Disability in Their Children Using World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Child and Youth Version Joined Body Functions and Activity Codes Related to Everyday Life, Clinical Medicine Insights: Pediatrics, 11, 1-11, 2017.

Crossref

Google Scholar

16. Kim, H. and Kim, K., Health-Related Quality-of-Life and Diabetes Self-Care Activity in Elderly Patients with Diabetes in Korea, Journal of Community Health, 42(5), 998-1007, 2017.

Google Scholar

17. Ko, J., Woo, J.H. and Her, J.G., The reliability and concurrent validity of the GMFCS for children with cerebral palsy, Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 23(2), 255-258, 2011.

Google Scholar

18. Mueller-Godeffroy, E., Thyen, U. and Bullinger, M., Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy: A Secondary Analysis of the DISABKIDS Questionnaire in the Field-Study Cerebral Palsy Subgroup, Neuropediatrics, 47(2), 97-106, 2016.

Crossref

Google Scholar

19. Oskoui, M., Coutinho, F., Dykeman, J., Jette, N. and Pringsheim, T., An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(6), 509-519, 2013.

Crossref

Google Scholar

20. Palisano, R., Rosenbaum, P., Walter, S., Russell, D., Wood, E. and Galuppi, B., Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 39(4), 214-223, 1997.

Crossref

Google Scholar

21. Park, E.Y., Path analysis of strength, spasticity, gross motor function, and health-related quality of life in children with spastic cerebral palsy, Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 70, 2018.

Crossref

Google Scholar

22. Rosenbaum, P., Paneth, N., Leviton, A., Goldstein, M., Bax, M., Damiano, D., Dan, B. and Jacobsson, B., A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(6), 480, 2007a.

Crossref

Google Scholar

23. Rosenbaum, P.L., Livingston, M.H., Palisano, R.J., Galuppi, B.E. and Russell, D.J., Quality of life and health-related quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(7), 516-521, 2007b.

Crossref

Google Scholar

24. Sakzewski, L., Carlon, S., Shields, N., Ziviani, J., Ware, R.S. and Boyd, R.N., Impact of intensive upper limb rehabilitation on quality of life: a randomized trial in children with unilateral cerebral palsy, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 54(5), 415-423, 2012.

Crossref

Google Scholar

25. Varni, J.W., Burwinkle, T.M., Berrin, S.J., Sherman, S.A., Artavia, K., Malcarne, V.L. and Chambers H.G., The PedsQL in pediatric cerebral palsy: reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the Generic Core Scales and Cerebral Palsy Module, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 48(6), 442-449, 2006.

Crossref

Google Scholar

26. Viehweger, E., Robitail, S., Rohon, M.A., Jacquemier, M., Jouve, J.L., Bollini, G. and Simeoni, M.C., Measuring quality of life in cerebral palsy children, Annales de Readaptation et de Medicine Physique, 51(2), 119-137, 2008.

Crossref

Google Scholar

27. Wang, H.Y., Cheng, C.C., Hung, J.W., Ju, Y.H., Lin, J.H. and Lo, S.K., Validating the Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life for Children (CP QOL-Child) questionnaire for use in Chinese populations, Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(6), 883-898, 2010.

Crossref

Google Scholar

28. Waters, E., Davis, E., Mackinnon, A., Boyd, R., Graham, H.K., Kai Lo, S., Wolfe, R., Stevenson, R., Bjornson, K., Blair, E., Hoare, P., Ravens-Sieberer, U. and Reddihough, D., Psychometric properties of the quality of life questionnaire for children with CP, Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49(1), 49-55, 2007.

Crossref

Google Scholar

29. Waters, E., Maher, E., Salmon, L., Reddihough, D. and Boyd, R., Development of a condition-specific measure of quality of life for children with cerebral palsy: empirical thematic data reported by parents and children, Child: Care, Health and Development, 31(2), 127-135, 2005.

Crossref

Google Scholar

30. Won, H.S., Sun, S., Choi, J.Y., An, H.J. and Ko, Y.H., Factors associated with treatment interruption in elderly patients with cancer, The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, 2018.

Crossref

31. Yang, Y.N., Kim, B.R., Uhm, K.E., Kim, S.J., Lee, S., Oh-Park, M. and Lee, J., Life Space Assessment in Stroke Patients, Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine, 41(5), 761-768, 2017.

Crossref

Google Scholar

32. Yim, S.Y., Yang, C.Y., Park, J.H., Kim, M.Y., Shin, Y.B., Kang, E.Y., Lee, Z.I., Kwon, B.S., Chang, J.C., Kim, S.W., Kim, M.O., Kwon, J.Y., Jung, H.Y., Sung, I.Y. and Society of Pediatric Rehabilitation and Developmental Medicine, Korea, Korean Database of Cerebral Palsy: A Report on Characteristics of Cerebral Palsy in South Korea, Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine, 41(4), 638-649, 2017.

Crossref

Google Scholar

PIDS App ServiceClick here!