eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

David Shin

, Youngjae Im

10.5143/JESK.2025.44.2.129 Epub 2025 May 02

Abstract

Objective: This paper examines whether women's human performance is suitable for the combat unit's commander positions.

Background: There has been a long debate about women's role in the military, mainly serving in specialties and positions that involve direct combat on the ground. The most controversial issue concerning women in the military is the integration of women into combat roles.

Method: The t-test and uniquely designed interaction assessment method were used to assess the occupational competence of men and women using the survey data of 964 enlistees in 51 combat units. Also, a semi-structured interview was conducted to evaluate the participation of women in the military qualitatively.

Results: The analysis results showed no difference in the occupational competence between men and women, except the artillery Army and infantry Marine.

Conclusion: It is concluded that women's physical fitness should not be the central issue in the debate of military person-job fit.

Application: This research is expected to contribute to the future discussions on the dynamics for the integration of women in the military.

Keywords

Human performance Occupational competence Military work Physical fitness

The most controversial issue concerning women in the military is the integration of women into combat roles.

The arguments against women's inclusion are based upon physical differences (Carr, 2020) that render women unfit for tasks. The ground combat is the most demanding military mission and tasks, including transport of wounded, movement in combat, dismounted attack in different terrain types, carrying heavy loads, ambush, and digging trenches (Larsson et al., 2020).

Those who opposed women serving in combat argued that "equal efforts" are not the same as "equal outcome" or "equal performance" because there is a physiological difference between men and women. Fenner and DeYoung (2001) argued that women are and will continue to be the weakest link in the chain and pointed that advocates for women's participation in ground combat have never demanded to raise women's physical training standards to be equal to those of men. On the other hand, proponents for the inclusion of women in combat roles emphasize that physical capability should not be the only determinant of combat effectiveness. They argue that factors such as leadership, decision-making, and psychological resilience also play a crucial role in military effectiveness (Kamarck, 2015). Further, the women's physical fitness has been positively affected by nutrition and medicine and greatly enhanced over the decades (Knapik et al., 2017). The most of women entering to the military training successfully completed all training courses the same as men, which ensures the necessary skills to perform a ground combat mission as a soldier.

Despite this debate, the primary research objective of this study is to assess whether occupational competence, which includes both physical and non-physical attributes, can provide a more holistic perspective on military performance rather than focusing solely on physical fitness. Fredenberg (2015) noted that the main concern for leadership in the military is about person-job fitness. Person-job fit is described as the capability of military forces to accomplish specified missions or goals (Schank et al., 1997). It is affected by the personnel qualifications, experience, availability of personnel, and overall cohesiveness of the unit. These factors are not mutually exclusive or independent of each other. The debate over the integration of women into non-traditional roles has been mainly about physical fitness.

However, this research argues that it should not be limited to physical fitness but includes other aspects required for ground combat. The idea of occupational competence, which is defined as "smoothly carrying out a role for a given mission on a personal and organizational level", was adopted. Further, we developed the assessment index of occupational competence that enables us to assess the physical fitness and the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for carrying out the military's mission, especially ground combat.

2.1 Theoretical background

To construct the assessment index of occupational competence, significant factors that are crucial to achieving and improving performance were identified first. The index must capture the nature of an individual's job or duty on the individual level as well as the ability to meet an organization's vision or goal on the organizational level.

In the South Korean military, women are mostly middle managers because they are commissioned as officers and non-commissioned officer. Their roles as supervisors include communicating effectively and presenting goals and courses of action; roles as subordinates include writing reports and coordinating activities (Jin, 2009). According to McClelland (1973), competence means the ability to respond to a specific pressure and respond to situations spontaneously, this includes communication, patience, appropriate goal setting, and self-development. In the Boyatzis (1982) competence model, competence is defined as general knowledge, skill, trait, motivation, self-image, or social role of an individual who is causally associated with dynamic behavior. Spencer and Spencer (1993) argued that competence consists of achievement motivation, stress coping, self-concept and value, self-confidence, analytic thinking, and conceptual thinking.

In the early 2000s, the Korean government created the government standard competency dictionary to enhance productivity and provide a concrete framework for staffing. It defines each competency's concepts and behavioral characteristics and identifies four significant elements: organizational commitment, information gathering and management, self-control, and communication (MIS, 2001). Further, Yoon (2012) created the assessment index composed of mission-performance, human relations, occupational awareness, and organizational commitment criteria.

2.2 Development of occupational competence index

2.2.1 Element of occupational competence

In order to develop the assessment index of occupational competence, this study first conducted an extensive review of existing occupational competence models to identify the key elements relevant to military tasks. These elements were categorized based on prior theoretical frameworks and refined through expert consultations. And comparative analysis of assessment frameworks used in the past two decades was conducted to ensure that the occupational competence model aligns with contemporary military needs. This process enabled the identification of previously unconsidered factors, which were incorporated into the final index. In particular, we tried to capture the concept of combat competence, which is related to actions in actual combat mission situations. It is the human factor's in-tangible characteristics that encompass knowledge, technology, and attitude, which can be trained through education and training (Choi, 2010).

As modern warfare grows increasingly complex, a multidimensional evaluation framework is necessary—one that integrates cognitive, physical, and psychological factors. Rather than introducing entirely new indices, this study synthesizes and reorganizes existing evaluation metrics from previous research to align with practical assessment objectives. By doing so, we aim to provide a structured and comprehensive approach to evaluating military officer performance, ensuring its applicability in contemporary operational environments. Given the complexity of modern warfare, evaluating military personnel requires a multidimensional approach that encompasses cognitive, physical, and psychological attributes. To address these aspects, combat command and situation judgment are critical for military officers as they frequently face high-stakes, ambiguous, and rapidly evolving scenarios. The ability to assess threats, make quick decisions under pressure, and adapt to dynamic conditions is well-documented in military leadership literature (Lawani et al., 2023; Thelma and Chitondo, 2024). Research on Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) supports the argument that experienced decision-makers rely on intuitive reasoning and pattern recognition in complex situations (Klein, 2008).

Combat stamina, training and psychological management encompass both physical endurance and resilience under combat conditions. Relevant studies indicate that high physical fitness levels contribute to improved cognitive performance, stress resilience, and overall combat effectiveness (Lieberman et al., 2016; Zueger et al., 2023). Additionally, the U.S. Army's Holistic Health and Fitness (H2F) program emphasizes the interplay between physical readiness and cognitive performance, highlighting the necessity of stamina in occupational competence. Professionalism, pride and loyalty are core characteristics of military officers, encompassing ethical decision-making, adherence to military doctrine, and leadership integrity. Related studies emphasize that strong professional identity enhances commitment, unit cohesion, and effectiveness in leadership roles (Paterson, 2019; Wong and Gerras, 2015). And, self-control and development play a significant role in military effectiveness, as it influences emotional regulation, stress management, and discipline. Research on self-regulation theories (Inzlicht et al., 2021) suggests that individuals with higher self-control exhibit better stress tolerance, reduced impulsivity, and enhanced leadership effectiveness. In high-pressure environments, such as combat situations, officers with strong self-control can maintain focus and make rational decisions under extreme stress (Taylor et al., 2019).

2.2.2 Definition of occupational competence

Military officers must understand complex strategic, cultural, and operational contexts while effectively communicating and persuading diverse stakeholders. This competency is especially relevant in modern warfare, where asymmetric threats, coalition operations, and civil-military interactions require a high level of interpersonal and negotiation skills (Duhé and Krsmanovic, 2024). Modern military operations require seamless coordination across various units, services, and even multinational forces. Coordination and integration refer to an officer's ability to align efforts, optimize resource utilization, and foster joint operations among diverse teams (Grey and Osborne, 2020).

Therefore, occupational competence is defined as "the ability to smoothly carry out a role for a given mission on a personal and organizational level." It includes the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for carrying out the mission in the military. Moreover, the military has an organizational specificity that requires individuals to cope with combat situations effectively. Thus, occupational competence is composed of the commander competence element and basic competence element. The commissioned officer's combat competence includes combat command, situation judgment, leading by example, combat stamina, combat training, and psychological management. General combat competence includes professionalism, self-control, loyalty, affection, pride, understanding and convincing, and coordination and integration. Table 1 provides the detailed definitions of factors included in the assessment of mission performance competence.

|

Factor |

Definition |

|

|

Commander |

Combat command (Lawani et al., 2023; Thelma and Chitondo,

2024) |

Ability to understand the unit's operational plan and effectively

lead the unit |

|

Situation judgment (Klein, 2008) |

Ability to identify key issues and make correct decisions in contingencies

or change of assignments |

|

|

Leading by example (Lawani et al., 2023; Thelma and Chitondo,

2024) |

Take the initiative and set an example to perform |

|

|

Combat stamina (Lieberman et al., 2016; Zueger et al., 2023) |

Physical abilities such as running, muscular strength, marches,

and overcoming obstacles |

|

|

Combat training psychological management |

Ability to identify and manage the emotional state |

|

|

Basic |

Professionalism (Paterson, 2019; Wong and Gerras, 2015) |

Have the necessary knowledge and skills to carry |

|

Self-control (Inzlicht et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2019) |

Ability to control the excessive workload and stress |

|

|

Loyalty (Paterson, 2019; Wong and Gerras, 2015) |

Attitudes that prioritize the achievement of the |

|

|

Affection (Duhé and

Krsmanovic, 2024) |

Positive Attitudes toward the organization's mission |

|

|

Pride (Paterson, 2019; Wong and Gerras, 2015) |

Attitudes to be proud of being a soldier or that |

|

|

Self-development (Inzlicht et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2019) |

Attitudes to improve one's expertise or skills for the |

|

|

Understanding and convincing (Duhé and

Krsmanovic, 2024) |

Ability to understand the intentions of the other |

|

|

Coordination and integration (Grey and Osborne, 2020) |

Ability to negotiate when there is a conflict of |

|

2.3 Evaluation of reliability and validity of occupational competence

The combat performance competence questionnaire includes the commander competence elements and basic competence elements to measure the overall combat performance competence. The occupational competence is assessed based on a 5-point Likert scale (1: very poor, 3: average, 5: very good). The weight of the assessment index was determined by questionnaires from 32 experts, including high-ranked officers, scholars, and government officials, and shown as follows. The weight of combat command, situation judgment, and leading by example is 0.21. The weight of combat stamina is 0.18. The weight of combat training and psychological management is 0.21. The weight of professionalism is 0.08. The weight of self-control is 0.08. The weight of loyalty and affection is 0.06. The weight of pride and self-development is 0.08. The weight of understanding and convincing and coordination and integration is 0.1. Then, the weight score is converted to a final score on a 1 to 100 scale.

We organized our data using a cross-sectional and categorical indexing method (Mason, 2002) to ensure the reliability and validity of the qualitative data. It allows for efficient retrieval of specific pieces of information, facilitates an interpretive reading of the data as the data are organized according to themes or subheadings, and assists in cross-checking between the research questions, data, and the analysis (Mason, 2002). The t-test and counting method were used to compare two groups. The t-test is a more general approach to compare two groups (Blair and Higgins, 1985). It is used to determine if there is a significant difference between the means of occupational competence scores. The statistical analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics 25 software package. Also, we counted the number of female or male commanders (leaders) with the lowest score in the comparison group.

The reliability and validity test were conducted on each questionnaire item to assure the analysis results' reliability and validity. First, a rating scale's reliability is related to the degree to which it produces consistent results when repeatedly measured with the same measurement tool, whether consistency or homogeneity among items when each item measures occupational competence. The Cronbach's α coefficient was used, which is most commonly used to test the internal consistency: how closely related to a set of items are as a group (Spiliotopoulou, 2009). Cronbach's α coefficient is 0.97. The higher the Cronbach's α coefficient value implies, the better internal consistency it has, but the Cronbach's α coefficient value higher than 0.6 is generally acceptable (Bland and Altman, 1997).

Second, the rating scale's validity is a process of reviewing whether the measurement results are accurate. If the constructive concept (commander competence element and basic competence element) is used to evaluate the occupational competence, items within the constructive concept should be highly correlated. The average variance extracted (AVE) value and construct reliability (CR) value was used to test the validity. The AVE value is 0.72 and 0.73 for the commander competence element and basic competence element, and the CR value is 0.93 and 0.96 for the commander competence element and basic competence element. The minimum threshold for the AVE and CR are 0.50 and 0.7, respectively (Garver and Mentzer, 1999; Gefen and Straub, 2005).

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Participants

The survey was conducted by 964 enlisted service members in entire echelons that women are assigned as a commander such as a squadron leader, platoon leader or company commander: 51 echelons total including the Army (29 echelons), Marine (13 echelons), and Air Force (9 echelons). A total of 48 service members (24 men and 24 women) from the various occupational specialty, including infantry, artillery, aviation, engineer, armor, intelligence, and communication were interviewed.

One hundred eighty-three commanders are subject to assessing the occupational competence, including 109 male commanders and 74 female commanders. Table 2 depicts the number of commanders by each division of the Korean military.

|

Army |

Marine |

Air force |

|

|

Commander (Leader) |

Men: 65, Women: 47 |

Men: 25, Women: 16 |

Men: 19, Women: 11 |

3.1.2 Experimental design

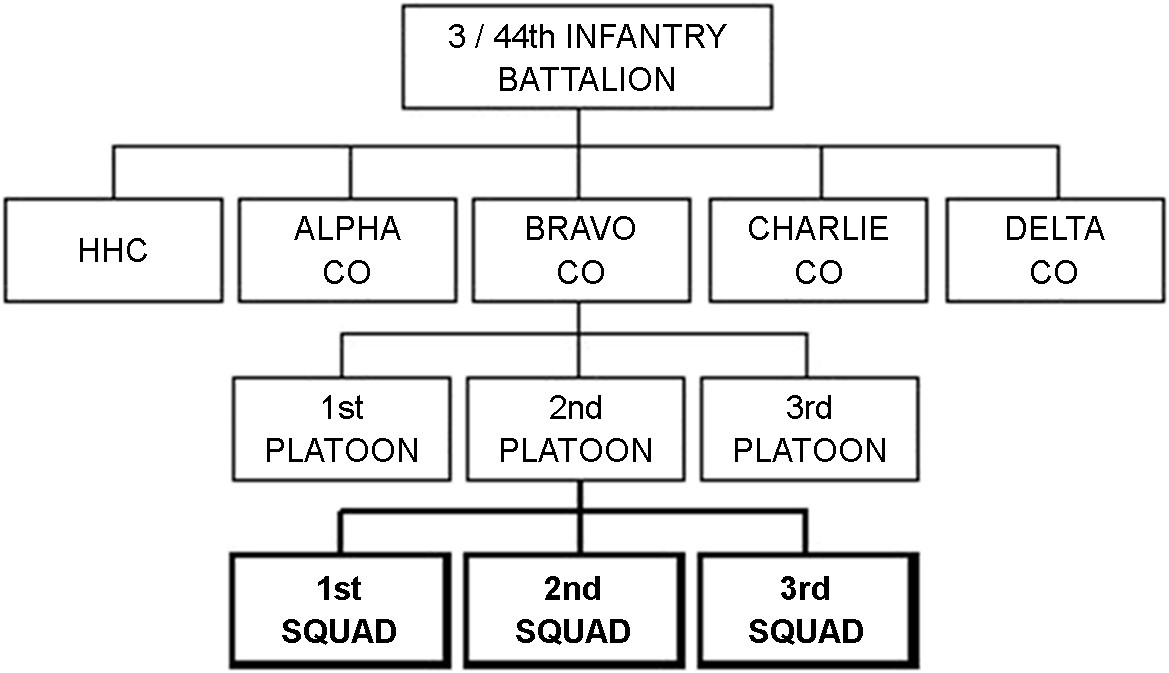

The military organization structure is as follows. The company consists of three platoon units, and the platoon consists of three squadrons, as shown in Figure 1. One squad consists of ten members. The assessment subjects are squadron leader, platoon leader, a company commander in each echelon, and the survey respondents are members belonging to each echelon. In other words, each squadron member is surveyed to evaluate each squadron leader, each platoon member is surveyed to evaluate each platoon leader, and each company member is surveyed to evaluate each company commander.

3.1.3 Analysis method

The assessment is made by comparing the occupational competence scores of female commanders with those of male commanders in the comparison group. For example, if the 1st squad has a female leader, the 1st squad leader's score is compared with the 2nd squad and third squad leaders' score. Furthermore, if the 1st platoon has a female leader, the 1st platoon leader's score received is compared with the 2nd platoon and third platoon leaders' score. Likewise, if the 1st company has a female commander, then the 1st company commander's score received is compared with the 2nd company and third company commanders' score.

Also, a semi-structured interview was conducted to capture and analyze opinions about women's employment in the military that the quantitative methods could not capture. A structured interview asks precisely the same questions in the same order to each interviewee, while an unstructured interview does not have a set of questions and flows like a conversation. A semi-structured interview falls somewhere between a structured and unstructured interview. A semi-structured interview is an interview in which there is no specific set of predetermined questions but has a framework of topics to be explored during the interview. It allows the interviewee to freely and honestly bring new ideas and has a high validity (Edwards and Holland, 2013). The questions like 1) how do you rate female commanders? 2) what is your opinion on the integration of women in the military, especially the ground combat? 3) What institutional arrangements do you feel are needed for the integration of women in the military? were used to guide the interview.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Assessment results

The main analytical point is the relative ranking of female commanders among all commanders by each echelon. The number of units in which the female commanders had the lowest ranking were counted and the average occupational competence score between male and female commanders by each branch were compared. Table 3 presents the results of the army commander's mission-performance assessment. The women's commander occupational competence is not different from that of the men. Among the 29 units surveyed, women are placed in the lowest ranking in 14 units, and men are placed in the lowest ranking in 15 units. Besides, female commanders placed in the lowest ranking received a reasonably good evaluation (75~80 points).

The t-test was conducted to examine whether there is a mean difference between men and women. The results show that the mean difference of occupational competence score is statistically significant in the artillery branch, officer (t=2.091, p=0.028) and artillery NCO (t=2.145, p=0.035). The mean difference of occupational competence score is also statistically significant in the aviation branch, officer (t=-3.492, p<0.01). In the infantry, engineer, and non-combat branches, there is no significant difference between the men and women.

|

Army |

Infantry |

Artillery |

Engineer |

Aviation |

Non-combat |

||

|

Officer |

NCO |

Officer |

NCO |

Officer |

Officer |

Officer |

|

|

# of comparison units |

7 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|

# of units that women |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

|

Men (Mean) |

78 |

82 |

75 |

80 |

88 |

79 |

89 |

|

Women (Mean) |

80 |

77 |

70 |

75 |

87 |

87 |

85 |

|

t-value |

-0.764 |

1.727 |

2.091 |

2.145 |

0.335 |

-3.492 |

1.612 |

|

p-value |

0.275 |

0.152 |

0.028 |

0.035 |

0.530 |

0.005 |

0.137 |

Table 4 presents the results of the Marine commander's mission-performance assessment. The results show that the occupational competence of women is much lower than men. Among the total of 13 units surveyed, women are placed in the lowest ranking in 10 units. Also, the average occupational competence scores of male officers and non-commissioned officers are higher in all branches. The t-test results show that the mean difference of occupational competence score is statistically significant in infantry branch, officer (t=5.874, p<0.001) and infantry NCO (t=5.792, p<0.001), but in the engineer branch, there was no significant difference between the men and women.

|

Marine |

Infantry |

Engineer |

|

|

Officer |

NCO |

NCO |

|

|

# of comparison units |

3 |

8 |

2 |

|

# of units that women

ranked the lowest |

2 |

7 |

1 |

|

Men (Mean) |

77 |

80 |

67 |

|

Women (Mean) |

61 |

65 |

64 |

|

t-value |

5.874 |

5.792 |

1.266 |

|

p-value |

0.000 |

0.000 |

0.204 |

Table 5 shows the assessment results of the Air Force commander's occupational competence. Among the total of 9 units surveyed, women are placed in the lowest ranking in 4 units. The t-test results show that the mean difference of occupational competence score is statistically significant in the air defense artillery branch, officer (t=2.307, p=0.037). In the NCO's air defense artillery and non-combat branch, there is no significant difference between the men and women.

|

Air force |

Air defense artillery |

Non-combat |

|

|

Officer |

NCO |

NCO |

|

|

# of comparison units |

1 |

1 |

7 |

|

# of units that women

ranked the lowest |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Men (Mean) |

76 |

79 |

84 |

|

Women (Mean) |

70 |

78 |

81 |

|

t-value |

2.307 |

0.341 |

1.185 |

|

p-value |

0.037 |

0.427 |

0.139 |

3.2.2 Results of semi-structured interview

Most commanders in the combat branch felt that female officers and non-commissioned officers currently assigned to the commander and leader position had proven their ability to lead the units, and there is not a big difference in the occupational competence between women and men. Most female interviewees in the combat branch also said that there is no significant difference in the occupational competence between women and men. They noted that men and women went through and completed the same training process for the commissioning, and thus, the physiological differences should not be an issue on person-job fit.

Nevertheless, some pointed out that the Ministry should be strict in culling personnel who have a problem with their fitness before the commissioning and thoroughly controlling and managing the training process. The training course is a gateway to becoming an officer or non-commissioned officer, because candidates learn basic skills, knowledge and leadership throughout the course. Interviewees observed that the goal of candidate training course was not strictly and equally applied to all candidates regardless of sex and felt that it was generous to women.

Most interviewees warned that a certain institutional measure created to bridge the physical gap between women and men could end up discriminating against men. Thus, many suggest establishing a gender-neutral physical requirement for each position. They think this would solve the concerns raised about sex differences in physical fitness and prevent discrimination against men. For example, a gender-neutral physical requirement would guarantee that only physically qualified personnel could fulfill the required standard and be assigned to a position.

One issue that arises is whether this type of screening is a feasible alternative. Some argue that this format is a preferable institutional alternative to demonstrating women's abilities while not discriminating against men. In addition, few interviewees felt that this would limit women's opportunities to participate in combat missions. Finally, most interviewees agreed that allowing women in the Korean Military is inevitable and would not be a serious threat to national security.

The key distinction of this study from previous research is the introduction of an occupational competence index that evaluates not only physical performance but also cognitive, leadership, and psychological resilience factors. Unlike prior models that primarily focused on physical capability as the primary determinant for combat effectiveness, this index provides a more comprehensive approach to assessing military personnel.

The mission-performance assessment results indicate that the differences in the mission-performance between women and men are not significant except for the Marine and artillery Army. This suggests that beyond physical fitness, other critical factors contribute to combat effectiveness, such as leadership capabilities, decision-making skills, and psychological resilience. These elements ensure competence for ground combat or command positions in combat units.

However, the results of the Marine and Artillery Army should not be overlooked. There was a difference in mission performance between women and men in these branches due to the highly demanding nature of their tasks, including dismounted attacks in varying terrain, carrying heavy loads, ambush scenarios, and trench digging. These findings highlight the need for institutional measures to ensure mission integrity while promoting effective gender integration. Women's leadership and training proficiency have often been underestimated due to gender stereotypes (Biernat et al., 1998; Rice et al., 1980). However, Boldry et al. (2001) demonstrated that gender differences in military settings do not negatively impact unit cohesion or interpersonal relationships.

Women are often recognized for their meticulous work ethic, detailed approach, and strong participation when given opportunities to demonstrate their abilities (Dohkgoh, 2002). They excel in personnel management and counseling due to high levels of empathy and communication skills. Additionally, their strong sense of responsibility ensures dedication to assigned tasks. In sum, the general perception of women in the military is mostly positive; thus, expanding women's employment in the military is unlikely to impose significant burdens on military operations.

Given the empirical evidence, it is essential to advocate for the expansion of female commanders' roles in mission participation and leadership responsibilities. Previous research highlights that diverse leadership enhances decision-making processes and overall unit performance (Brown and Taylor, 2021). Moreover, contemporary military strategies emphasize inclusivity and talent optimization, reinforcing the argument for removing existing barriers to female officers' career progression (Olubiyo, 2024). The underrepresentation of female officers in high-responsibility positions often stems from structural and cultural biases rather than competence-based limitations. Studies have shown that when provided equal opportunities, female commanders perform on par with their male counterparts, contributing effectively to military objectives (Williams and Carter, 2023). Expanding their participation in leadership roles can strengthen operational effectiveness and foster a more equitable professional environment.

However, the military must ensure this would not damage military work and effectiveness because the results show that compared to men, women's mission performance competence scores are significantly lower in the Marine and artillery Army. This can be interpreted as being due to the high physical fitness required for the mission in those two branches and implies that some areas require special effort for gender integration. Relevant research (King, 2015; Moore, 2017) also revealed that integration of women into the combat and their possible acceptance not just as equivalents but as equals on a physical fitness.

Implementing a gender-neutral physical requirement may be one solution to barriers women face when entering the Korean military. Required specialties and abilities from assignments by each branch of the military service are different. Thus, identifying those specialties and abilities and adding them to the evaluation as a qualification requirement can ensure only candidates meet the qualification requirements. It will eliminate candidates who lack qualifications and competence. Of course, this can ensure that only qualified and competent candidates can enter military branches that require significant physical challenges. Most women in the military agree on adding the qualification requirement to the evaluation. This new evaluation system will be a steppingstone to prove women's competence and lessen some men's prejudice against women's potential to perform in mission combat. It should help eliminate concerns that arise from women's employment in all combat positions and ensure military work and effectiveness.

Academically, this study advances the discussion on gender integration in the military by offering a validated framework for evaluating competence in combat roles. Methodologically, it expands the scope of military assessment beyond traditional fitness metrics by incorporating leadership, adaptability, and decision-making skills. Practically, the findings support the argument that women's suitability for military roles should not be solely determined by physical fitness but should consider broader occupational competencies.

This paper contributes to a growing body of literature that addresses the integration of women in the military. It adopts the idea of occupational competence to understand the integration of women into ground combat roles. This paper especially sheds light on the military person-job fit affected by the integration of women into non-traditional roles and a better understanding of the potential role of women in the military. Although the debate on women's employment in the military is far from over, this study suggests that occupational competence should be the primary criterion for role assignment rather than gender alone. The results also indicate that concerns about women's ability to perform in military roles may be overstated, except in physically intensive branches such as the Marine Corps and Artillery Army. Therefore, military policymakers should consider gender-neutral standards for recruitment and training to optimize personnel effectiveness.

References

1. Biernat, M., Crandall, C.S., Young, L.V., Kobrynowicz, D. and Halpin, S.M., All that you can be: Stereotyping of self and others in a military context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(2), 301, 1998.

Google Scholar

2. Blair, R.C. and Higgins, J.J., Comparison of the power of the paired samples t test to that of Wilcoxon's signed-ranks test under various population shapes. Psychological Bulletin, 97(1), 119, 1985.

Google Scholar

3. Bland, J.M. and Altman, D.G., Statistics notes: Cronbach's alpha. Bmj, 314(7080), 572, 1997.

Google Scholar

4. Boldry, J., Wood, W. and Kashy, D.A., Gender stereotypes and the evaluation of men and women in military training. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 689-705, 2001.

Google Scholar

5. Boyatzis, R.E., The competent manager: A model for effective performance. John Wiley & Sons, 1982.

Google Scholar

6. Brown, T. and Taylor, M., Diversity in Military Leadership: Strengthening Decision-Making and Unit Performance. Journal of Military Studies, 29(4), 112-127, 2021.

7. Carr, A.D., An exploration of gender and national security through the integration of women into military roles. Pepperdine Policy Review, 12(1), 2, 2020.

Google Scholar

8. Choi, K.H., Development and Validation of Selection Battery for Cadets. The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 25(4), 145-186, 2010.

9. Dohkgoh, S., Key Issues and Role Expectations for Using Women's Military. The Quarterly Journal of Defense Policy Studies, 17, 61-86, 2002.

10. Duhé, C.H. and Krsmanovic, M., Recruitment and retention of active military and veteran students at community colleges. Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 31(1), 121-136, 2024.

Google Scholar

11. Edwards, R. and Holland, J., What is qualitative interviewing? A&C Black, 2013.

Google Scholar

12. Fenner, L.M. and DeYoung, M.E., Women in combat: Civic duty or military liability? Georgetown University Press, 2001.

Google Scholar

13. Fredenberg, M., Putting Women in Combat Is an Even Worse Idea Than You'd Think. National Review, 15, 2015.

14. Garver, M.S. and Mentzer, J.T., Logistics research methods: employing structural equation modeling to test for construct validity. Journal of Business Logistics, 20(1), 33, 1999.

Google Scholar

15. Gefen, D. and Straub, D., A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 5, 2005.

Google Scholar

16. Grey, D. and Osborne, C., Perceptions and principles of personal tutoring. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(3), 285-299, 2020.

Google Scholar

17. Inzlicht, M., Werner, K.M., Briskin, J.L. and Roberts, B.W., Integrating models of self-regulation. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 319-345, 2021.

Google Scholar

18. Jin, J.S., A study on the performance enhancement of assessment centers for public servants. Korean Journal of Public Administration, 47(3), 139-163, 2009.

19. Kamarck, K.N., Women in combat: Issues for Congress, 2015.

20. King, A.C., Women warriors: Female accession to ground combat. Armed Forces & Society, 41(2), 379-387, 2015.

Google Scholar

21. Klein, G., Naturalistic decision making. Human Factors, 50(3), 456-460, 2008.

Google Scholar

22. Knapik, J.J., Sharp, M.A. and Steelman, R.A., Secular trends in the physical fitness of United States Army recruits on entry to service, 1975-2013. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(7), 2030-2052, 2017.

Google Scholar

23. Larsson, J., Dencker, M., Bremander, A. and Olsson, M.C., Cardiovascular responses of load carriage in female and male soldiers. 5th International Congress on Soldiers physical performance (ICSPP 2020), Quebec City, Canada, 11-14, 2020.

Google Scholar

24. Lawani, A., Flin, R., Ojo-Adedokun, R.F. and Benton, P., Naturalistic decision making and decision drivers in the front end of complex projects. International Journal of Project Management, 41(6), 102502, 2023.

Google Scholar

25. Lieberman, H.R., Bathalon, G.P., Falco, C.M., Kramer, F.M., Morgan, C.A. and Niro, P., Severe decrements in cognition function and mood induced by sleep loss, heat, dehydration, and undernutrition during simulated combat. Biological Psychiatry, 47(6), 485-498, 2016.

Google Scholar

26. Mason, J., Qualitative researching. Sage, 2002.

27. McClelland, D.C., Testing for competence rather than for" intelligence." American Psychologist, 28(1), 1, 1973.

Google Scholar

28. MIS, Standard Competence Dictionary. In Standard Competence Dictionary, 2001.

29. Moore, B.L., Introduction to Armed Forces & Society: Special issue on women in the military. In: SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 2017.

Google Scholar

30. Olubiyo, K.G., Breaking Gender Walls: Understanding the Changing Roles of Women in the Nigerian Armed Forces. Gender and Women's Studies, 5(2), 2, 2024.

Google Scholar

31. Paterson, P., Measuring military professionalism in partner nations: Guidance for security assistance officials. Journal of Military Ethics, 18(2), 145-163, 2019.

Google Scholar

32. Rice, R.W., Bender, L.R. and Vitters, A.G., Leader sex, follower attitudes toward women, and leadership effectiveness: A laboratory experiment. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(1), 46-78, 1980.

Google Scholar

33. Schank, J.F., Harrell, M.C., Sollinger, J.M., Pinto, M.M. and Thie, H.J., Relating Resources to Personnel Readiness. In: Rand Corporation, 1997.

Google Scholar

34. Spencer, L. and Spencer, S., Competence at work. John Wiley & Sons. Inc: 1993.

35. Spiliotopoulou, G., Reliability reconsidered: Cronbach's alpha and paediatric assessment in occupational therapy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 56(3), 150-155, 2009.

Google Scholar

36. Taylor, M.K., Shipherd, J.C., Pruitt, J.M. and Lieberman, H.R., Stress, resilience, and performance: A review with implications for the military operational environment. Military Medicine, 184(7-8), e234-e240, 2019.

37. Thelma, C.C. and Chitondo, L., Leadership for sustainable development in Africa: A comprehensive perspective. International Journal of Research Publications, 5(2), 2395-2410, 2024.

Google Scholar

38. Williams, C. and Carter, L., Equal Opportunity in Military Command: Policy and Practice. Armed Forces Review, 31(2), 78-95, 2023.

39. Wong, L. and Gerras, S.J., Lying to ourselves: Dishonesty in the Army profession. Strategic Studies Institute, 2015.

Google Scholar

40. Yoon, Y.M., An empritical research on improving work-performing abilities and attitude of Korean female navy officers, Yonsei University, 2012.

41. Zueger, R., Niederhauser, M., Utzinger, C., Annen, H. and Ehlert, U., Effects of resilience training on mental, emotional, and physical stress outcomes in military officer cadets. Military Psychology, 35(6), 566-576, 2023.

Google Scholar

PIDS App ServiceClick here!