eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

eISSN: 2093-8462 http://jesk.or.kr

Open Access, Peer-reviewed

Chi Nhan Huynh

, Younghwan Pan

10.5143/JESK.2025.44.6.747 Epub 2026 January 02

Abstract

Objective: This paper proposes a framework to help UI designer utilize AI for maintaining visual consistency in user interface (UI) design.

Background: UI consistency plays a critical role in user experience by improving predictability, usability, and visual coherence across digital products. Traditional methods for ensuring consistency (heuristic evaluation, cognitive walkthrough, formal usability, pluralistic walkthrough, feature inspection, consistency inspection, and standards inspection) are widely used despite being time-consuming and resource-intensive. With the rise of AI in design, there is growing interest in how these technologies can support consistency. However, AI used in past researches remains unavailable to the majority of designers.

Method: The framework was created through pairing AI available as plugins in Figma with a three-part taxonomy (physical, communicational, conceptual) inside an industry-standard design environment. To evaluate the framework, a set user interfaces were designed following our framework is compared with three other sets with varying inconsistencies. Afterwards, forty UI/UX designers were asked to finish a set of tasks to probe for the user experience across three key areas: task completion time, clarity rate, and satisfaction.

Results: Results revealed that our proposed AI-assisted framework improves core UX outcomes by enabling designers to maintain higher consistency using accessible AI tools integrated into standard workflows.

Conclusion: The framework successfully addresses the gap between AI application in research and design practice by pairing accessible, Figma-integrated tools into a three-part consistency framework. By combining AI-supported checks with manual reviews, teams can cut post-design effort while maintaining review depth and reliability. Future development should focus on expanding the sample size for better validity, as well as updating AI technology as needed.

Application: This framework can be adopted by UI designers seeking to utilize AI for UI consistency. It is especially useful for product teams during post-design audits.

Keywords

UI consistency Design systems Visual audit Human-AI

Maintaining visual consistency in user interface (UI) design is a crucial factor for ensuring a seamless and intuitive user experience. Consistency supports learnability, predictability, and aesthetic harmony across digital products, helping users build mental models and navigate with ease. As digital interfaces become more complex and design teams grow, preserving consistency across screens, states, and updates becomes an increasingly difficult task. Despite its importance, ensuring UI consistency remains a persistent challenge among design teams.

Traditionally, designers rely on heuristic evaluation, cognitive walkthrough, formal usability, pluralistic walkthrough, feature inspection, consistency inspection, and standards inspection to assess the consistency and usability of interfaces (Nielsen, 1994). Despite being often time-consuming and resource intensive, these evaluation methods remained foundational in post-design audit activities (Viswanathan and Peters, 2010; Ivory and Hearst, 2001). As such, recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have focused on new possibilities for supporting UI design processes. A growing body of research has experimented with leveraging AI to detect design guideline violations, evaluate layout structures, or even generate consistent components and visual elements based on style input (Zhao et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021; McNutt et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2025). However, the majority of AI developed in prior works remains either under construction or unavailable for public uses, leaving practitioners without a clear pathway to integrate AI throughout the design lifecycle (Bertão and Joo, 2021; Lu et al., 2022; He and Yang, 2020).

In response to this gap, this paper proposes and empirically evaluates a new framework that aims to guide designer to better leverage AI tools assistance for UI consistency. To be specific, our framework pairs traditional manual methods with available AI capabilities in three consistency dimensions (physical, communicational and conceptual), focusing on widely accessible, plugin-based tools integrated into standard platforms such as Figma. To evaluate the efficiency and practicality of this framework, a case study was conducted to compare different sets of user interface across key user experience elements.

User Interface (UI) consistency is an important aspect that affects the user experience. Ant Ozok and Salvendy (2000) measured consistency through 3 areas: Physical consistency, Communicational consistency, and Conceptual consistency. Physical consistency refers to the uniformity of the UI's appearance (spacing, symbol, label, location, shape, size, color). Communicational consistency concerns itself with how the user interacts with the system, such as menu, between-task consistency, distinction of text & object, and hyperlink. Conceptual consistency pertains to the alignment of visual and semantic elements with domain conventions. Given this context, priors studies have found correlations between inconsistency in interface and several aspects of user experience (error rate, completion time, satisfaction). Error rate is noted as the primary impact, with physical inconsistencies, particularly those related to fonts and locations, having a strong influence on the number of errors (AlTaboli and Abou-Zeid, 2007). Completion time is also a strong indication, as inconsistency weakens generalization, making it harder for users to recall or infer correct procedures. Specifically, Kellogg (1987) and Finstad (2008) found in their studies that for casual users, superficial similarities to familiar interfaces can be misleading, resulting in incorrect task transfer and substantially slower completion times when the underlying structure differs. These inconsistencies result in lower satisfaction levels, with users commonly reported feeling frustrated, incompetent, and unproductive, and viewing the system as undependable or unfriendly (Ant Ozok and Salvendy, 2000; Kellogg, 1987).

According to Viswanathan and Peters (2010) and Ivory and Hearst (2001), consistency checks are typically conducted manually toward the end of the design process. However, these late-stage reviews are often time-consuming, error-prone, and risk overlooking subtle inconsistencies that could negatively affect the user experience. Given the importance of consistency, the topic of consistency-maintaining methods was researched extensively. Notably, Nielsen (1994) outlined 7 main methods: heuristic evaluation, cognitive walkthrough, formal usability, pluralistic walkthrough, feature inspection, consistency inspection, and standards inspection. Over time, the classification and application of UI consistency evaluation methods have evolved, with subsequent authors expanding and refining earlier frameworks. For example, Simpson (1999) extended consistency inspection and standard inspection as part of conformancy assessment, a process to manage consistency and adherence to style guides through identifying and assessing design deviations. The establishment of conformancy procedures ensures that project personnel, who might otherwise seek shortcuts due to time and cost pressures, do not neglect their responsibilities regarding adherence to the Style Guide and usability. Similarly, with the widespread adoption of Agile and Lean frameworks in software development, research increasingly focused on strategies to reduce the resources required for consistency audits during the post-design phase. As such, method such as pluralistic walkthrough was transformed into multiple design review sessions. By increasing the amount of testing time, these methods are able to cut corners and eliminate the need to test with real users.

Recent research has begun exploring how AI can assist in achieving or evaluating UI consistency. One direction involves using machine learning to detect inconsistencies in layouts, spacing, or visual style. Zhao et al. (2020) provided developers with a computer-vision based adversarial autoencoder to detect and fix GUI animations that violates UI design guidelines. Similarly, Yang et al. (2021) trained a computer network on Google's Material guideline in order to detect UI violations. McNutt et al. (2024) integrates visualization tool with a GUI-based color palette linter, allowing the users to define linting rules to check for color palette and other areas of accessibilities. Xu et al. (2025) utilizes ChatGPT to review and fix codes that doesn't follow UI design system.

Despite these advances, adoption rate in practice remains low (Bertão and Joo, 2021; Lu et al., 2022; He and Yang, 2020). Bertão and Joo (2021) noted that a fundamental source of the research-practice gap lies in the unavailability and limited accessibility of research-developed AI systems and tools to industry practitioners. This then prompted researchers to use analytical frameworks typically applied to the adoption of "soon-to-be-launched products" to understand designers' perspectives on currently available AI tools. Additionally, most ML models often act to replace human designers on tasks and fail to create applications that utilize designers' agency and creativity (Lu et al., 2022). This results in a constant struggle between designers and AI tools when trying to implement them into design workflows.

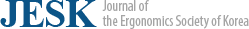

Previous literature has identified that the process of checking for errors in design is often labor-intensive and time-consuming. To address this challenge, our goal is to create a framework (Figure 1) so designers can better utilize AI in streamlining consistency checks. We began by examining how consistency is typically categorized in the literature. While many sources divide consistency into types such as visual, functional, internal, and external, we found that these categories can be too broad or include aspects beyond a designer's direct control. For example, functional consistency often depends on developers catching bugs, which is not always within the designer's scope during the ideation phase.

To provide a more actionable framework, we adopted a more detailed division of consistency into physical, communicational, and conceptual categories. To clarify this approach, we compile from past literatures all the methods designers use to achieve consistency and assigned each method to its respective category (Table 1).

|

Physical consistency checking

methods |

Conformancy assessment, Heuristic evaluation |

|

Conceptual consistency checking

methods |

Usability testing, Design review sessions and standup meetings |

|

Communicational consistency checking

methods |

Design review sessions and standup meetings, Cognitive walkthrough |

After categorizing these methods, we identified and paired AI tools that could support each group. We focused on AI tools that can be integrated into an industry-standard design platform such as Figma, to ensure that the recommended tools are both practical and widely accessible for designers. For instance, we found that physical consistency checking methods can benefits greatly from tools that leverage Large Vision Model, which can compare previously-designed UI screens in a given design file to spot inconsistencies in style. Unfortunately, no design-file-wide LVM tools as such is available currently in the form of plugin. However, less complexed LVM plugins such as Helper can still be leveraged as it can scan for inconsistency within a design screen.

Another popular option other than Large Vision Model is Large Language Model. We found that LLM such as ChatGPT can help bridge the gap between user expectations and design logic. In the case of conceptual consistency checking, we suggested the use of ChatGPT to generate testable requirements directly from user stories, ensuring that conceptual goals are clearly defined and measurable.

Lastly, in the area of communication consistency checking, AI can be trained on neuroscience research to mimic human visual attention and perception. As such, plugin such as VisualEyes can be used to simulate where users are likely to focus their attention on a design, providing insights that teams can discuss during review sessions.

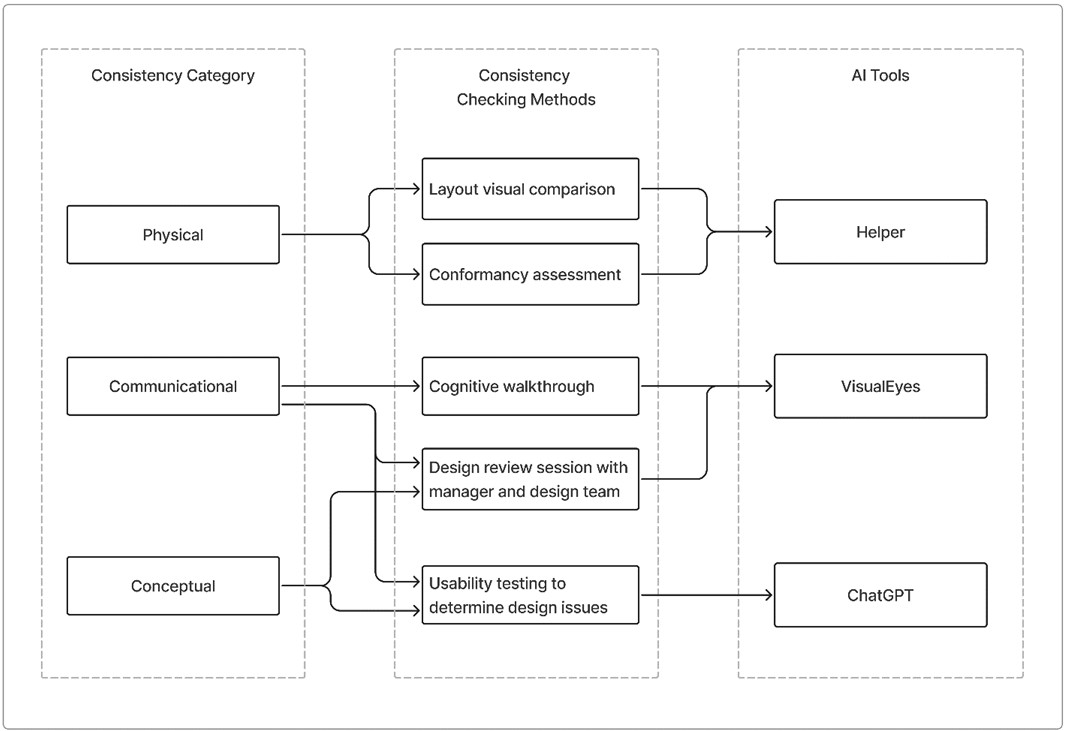

We argue that designing an interface in accordance with our framework, thereby enhancing its consistency, is expected to yield improvements in fundamental user experience metrics. Specifically, a more consistent interface is anticipated to facilitate reduced task completion times, higher rates of task success, and increased user satisfaction, in comparison to interfaces that exhibit inconsistencies. As such, in order to test the efficiency and practical value of our framework, we devised an experiment to determine whether user interfaces designed using our framework result in improved key user experience dimensions, compared to interfaces that contain inconsistencies.

4.1 Experimental design

To ensure that the experiment accurately measures the impact of consistency on user experience, a set of designs of a booking app was chosen. This domain was selected because it is sufficiently unfamiliar to most users, thereby requiring them to actively interpret visual elements and textual information on the interface to complete the tasks, rather than relying on prior knowledge or habitual patterns. The booking app was divided into four groups:

- Group 1 (Consistent UI): Designed using the framework's AI-assisted framework, ensuring consistency in all dimensions.

- Group 2 (Physical Inconsistency): Deliberate mismatches in component sizes, colors, and alignment.

- Group 3 (Communicational Inconsistency): Unpredictable menu behaviors and feedback mechanisms.

- Group 4 (Conceptual Inconsistency): Non-standard labels (e.g., "Transmit" instead of "Submit") and ambiguous icons.

To create these four groups, we first began by designing a set of UI screens for a booking app. Afterwards, we utilized each appropriate AI tools to each for its corresponding inconsistencies. For physical consistency checks, target frames were selected and scanned using Helper's default rules to flag deviations in color styles, typography scales, spacing tokens, and component overrides, with the resulting issue list exported and retained issues defined as those appearing in at least two out of three repeated scans on the same snapshot. For conceptual consistency, Visualeyes was installed and ran on the selected frames to generate attention heatmaps under default viewing assumptions. For conceptual consistency, screenshots of the UIs were taken and uploaded to ChatGPT. Chain-of-Thoughts prompting technique was used, where additional parameters and examples were given to the LLM to ensure repeatability (Pereira et al., 2025). In our case, we asked the agent to play the role of a designer who is checking for consistency during post-design audits. Additionally, we also specify the task of the model to produce a standard story sentence ("As a [user], I want [goal], so that [value]"), alongside with its acceptance criteria. The final product is a set of screens that is consistent across all three dimensions.

Subsequently, groups with inconsistencies were created by selectively withholding checks for the targeted dimension while maintaining the others. For example, for group 2 with only physical inconsistencies, the physical consistency audit was intentionally omitted during revision, whereas communicational and conceptual checks proceeded as specified. The same procedure was used to isolate communicational–only and conceptual–only inconsistencies.

In prior literatures, three key UX elements (task completion time, rate of task success, and satisfaction rate) were identified to be significantly impacted by changes in consistency. With this basis, these key UX elements were compared between the four groups, thereby testing the efficiency of our framework (as illustrated in Figure 2).

Following this, we seek to validate several hypotheses:

- H1: Group 1 exhibit faster task completion times than UIs with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies (Groups 2-4).

- H2: Group 1 achieve higher clarity rates than UIs with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies (Groups 2-4).

- H3: Group 1 receive higher user satisfaction ratings than UIs with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies (Groups 2-4).

- H4: The effects of physical, communicational, and conceptual inconsistencies on task time, clarity rate, satisfaction, and perceived consistency will not differ statistically.

- H4 null: At least one inconsistency type (physical, communicational, conceptual) will exert a significantly larger negative effect on usability outcomes than the others.

4.2 Participants

The experiment involved 40 designers with varying levels of experience, evenly divided into 4 groups of 10 to ensure demographic balance and mitigate confounding variables. This mixed seniority level was selected to avoid bias from expertise. No counterbalancing was applied, as each participant experienced only a single condition.

4.3 Experiment procedure

Prior to the start of the study, participants were given a brief introduction outlining the purpose of the study and the general context of the booking app, but no detailed instructions or training on how to use the interface were provided. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of four groups, with each group interacting with a different version of the user interface - fully consistent, physically inconsistent, communicationally inconsistent, or conceptually inconsistent.

Each participant was then asked to complete a series of two tasks in sequence: Booking an appointment for 1 person on the date of 06/06, and modifying the booking date to 06/08 afterwards. The task completion time for each task recorded and summed up at the end of the session. Upon the completion of both tasks, participants were then given a survey (see Appendix), which was adapted using the System Usability Scale (Brooke, 1996). To be more specific, clarity rate was probed using a series of yes/no questions about whether participants felt confused on specific screens where inconsistencies were intentionally introduced, with "yes" was coded as 0 (indicating confusion) and "no" as 1 (indicating no confusion). Additionally, satisfaction was also assessed on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("Strongly Disagree") to 5 ("Strongly Agree"). All questions were made sure to be in the same direction so as to be calculated by means of averaging afterwards.

Given the modest sample size (N = 40), distributional assumptions were assessed prior to inference (see Table 2). Task completion time satisfied normality within each group (all p > .05), whereas clarity rate and perceived consistency violated normality in several groups (some p < .05).

|

Group |

Statistic |

df |

Sig. |

|

|

Task completion time |

Full consistency |

.891 |

10 |

.176 |

|

Physical inconsistent |

.937 |

10 |

.521 |

|

|

Communicational inconsistent |

.953 |

10 |

.703 |

|

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

.883 |

10 |

.140 |

|

|

Clarity rate |

Full consistency |

.833 |

10 |

.036 |

|

Physical inconsistent |

.911 |

10 |

.287 |

|

|

Communicational inconsistent |

.713 |

10 |

.001 |

|

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

.885 |

10 |

.149 |

|

|

Satisfaction |

Full consistency |

.911 |

10 |

.291 |

|

Physical inconsistent |

.965 |

10 |

.843 |

|

|

Communicational inconsistent |

.936 |

10 |

.510 |

|

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

.825 |

10 |

.029 |

|

Accordingly, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis analysis (Table 3) were conducted. Test results indicated significant group differences for task completion time (χ2 = 11.264, p = .010), clarity rate (χ2 = 14.409, p = .002), and satisfaction (χ2 = 12.053, p = .007).

|

|

Task completion time |

Clarity rate |

Satisfaction |

|

Chi-Square |

11.264 |

14.409 |

12.053 |

|

df |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Asymp. Sig |

.010 |

.002 |

.007 |

Post hoc pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests (Table 4) further clarify these results. For task time, Group 1 was significantly faster than Physical (U = 18.5, p = .017), Communicational (U = 11, p = .003), and Conceptual (U = 16, p = .010). No pairwise differences emerged among the three inconsistent groups (all p > .017), suggesting comparable slowdowns from physical, communicational, and conceptual inconsistencies.

|

Group |

Mann-Whitney U |

Asymp. Sig (2-tailed) |

|

Full consistency |

18.5 |

.017 |

|

Physical inconsistent |

||

|

Full consistency |

11.0 |

.003 |

|

Communicational inconsistent |

||

|

Full consistency |

16.0 |

.01 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

||

|

Physical inconsistent |

45.5 |

.732 |

|

Communicational inconsistent |

||

|

Physical inconsistent |

39.5 |

.426 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

||

|

Communicational inconsistent |

39.5 |

.425 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

Clarity rate's result (Table 5) mirrored this pattern: Group 1 outperformed Physical (U = 17.0, p = .008), Communicational (U = 7.5, p = .001), and Conceptual (U = 18.5, p = .012), while differences among the inconsistent groups were nonsignificant (all p > .017).

|

Group |

Mann-Whitney U |

Asymp. Sig (2-tailed) |

|

Full consistency |

17.0 |

.008 |

|

Physical inconsistent |

||

|

Full consistency |

7.5 |

.001 |

|

Communicational inconsistent |

||

|

Full consistency |

18.5 |

.012 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

||

|

Physical inconsistent |

34.5 |

.213 |

|

Communicational inconsistent |

||

|

Physical inconsistent |

46.5 |

.779 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

||

|

Communicational inconsistent |

31.5 |

.131 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

Satisfaction results (Table 6) were consistent with the above: participants rated the fully consistent UI higher than Physical (U = 13.5, p = .006), Communicational (U = 14.5, p = .007), and Conceptual (U = 13.0, p = .004), with no significant differences among the three inconsistent UIs (all p > .017).

|

Group |

Mann-Whitney U |

Asymp. Sig (2-tailed) |

|

Full consistency |

13.5 |

.006 |

|

Physical inconsistent |

||

|

Full consistency |

14.5 |

.007 |

|

Communicational inconsistent |

||

|

Full consistency |

13 |

.004 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

||

|

Physical inconsistent |

48.0 |

.879 |

|

Communicational inconsistent |

||

|

Physical inconsistent |

40.5 |

.471 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

||

|

Communicational inconsistent |

43.5 |

.619 |

|

Conceptual inconsistent |

Overall, there are statically significant results indicating that the fully consistent UI (Group 1) outperforms inconsistent variants on multiple UX metrics, which supports the following hypotheses:

- H1: Group 1 exhibit faster task completion times than UIs with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies (Groups 2-4).

- H2: Group 1 achieve higher clarity rates than UIs with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies (Groups 2-4).

- H3: Group 1 receive higher user satisfaction ratings than UIs with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies (Groups 2-4).

Additionally, there is no statistical evidence that one inconsistency type impairs outcomes more than the others. As such, the null hypothesis is rejected and the following hypothesis is accepted:

- H4: The effects of physical, communicational, and conceptual inconsistencies on task time, clarity rate, satisfaction, and perceived consistency will not differ statistically.

The findings demonstrate that our proposed AI-assisted framework improves core UX outcomes by enabling designers to maintain higher consistency using accessible AI tools integrated into standard workflows. Through our experiment, we found that the interface designed with our framework produced faster completion times, higher task accuracy, and greater satisfaction than interfaces with physical, communicational, or conceptual inconsistencies. As such, the present work specifies an operational path: in the post-design review phase, leveraging AI-assisted checks in conjunction with manual inspection can reduce designer effort while preserving and improving the reliability of identifying inconsistency issues, functioning as a complement rather than a replacement for expert evaluation and usability testing. Additionally, we also extended Ant Ozok and Salvendy framework by examining the relationship between different types of inconsistency. The results also indicate that addressing all three consistency dimensions is comparably important for preserving the user experience. We also provided evidence showing that no one inconsistency type impacted the user experience more than the others. Theoretically, this result affirms the importance of consistency, supporting the view that consistency reduces cognitive load and supports key UX aspects.

Ultimately, our study aims to provide designers with widely-available AI options to apply in their workflow and, to this end, measure the efficiency of said framework. As such, the study's primary limitation is that the interfaces were designed by the research team rather than by practitioners applying the framework themselves, and practicing designers only evaluated the resulting UIs instead of using the framework during design. Subsequent work should recruit designers to use the framework while creating interfaces and then have a separate set of participants judge those artifacts, enabling stronger inferences about the framework's effectiveness in realistic conditions and reducing same-source bias in design and evaluation roles. This could be remedied through expanding the sample size to a larger and more diverse cohort in order to allow assessment of differential benefits and learning curves across experience level and contexts. In addition to outcome metrics, capturing designers' thoughts while applying the framework would yield constructive feedback, thereby informing framework refinements grounded in practitioner experience. Additionally, our experiment did not incorporate any counterbalancing methods when dividing participants into groups as each participant experienced only a single condition. While random assignment reduces risk of participant-related confounds, the absence of counterbalancing means that any systematic task order effects could not be evaluated. Adopting within-subjects or repeated-measures designs should incorporate counterbalancing to better control for such potential confounds. Finally, we acknowledged that, due to the inconsistent nature of Generative AI technology, the result from our experiment is not completely reproducible. As such, future researches should pay close attention to this drawback, and document all settings used where appropriate.

Our study identified the growing gap between AI demonstrated in prior research and practical workplace adoption due to availability. Through the process of employing AI available as plugins in Figma and pairing it with a three-part taxonomy (physical, communicational, conceptual) inside an industry-standard design environment, this study provides a more accessible framework for designer to utilize AI tools in their works. To this end, design teams can reduce review effort and resources spent during post-design activities by leveraging AI-supported checks in conjunction with manual reviews. Additionally, our proposed approach offers flexible adoption in teams with mixed experience, helping less-experienced designers surface issues systematically while enabling senior practitioners to concentrate on higher-order decisions.

References

1. AlTaboli, A. and Abou-Zeid, M.R., "Effect of physical consistency of web interface design on users' performance and satisfaction", Proceedings of the International Conference on Human–Computer Interaction (pp. 849-858), 2007.

Google Scholar

2. Ant Ozok, A. and Salvendy, G., Measuring consistency of web page design and its effects on performance and satisfaction, Ergonomics, 43(4), 443-460, 2000. doi:10.1080/001401300184332.

Google Scholar

3. Bertão, R.A. and Joo, J., "Artificial intelligence in UX/UI design: a survey on current adoption and [future] practices", Proceedings of the Safe Harbors for Design Research (pp. 1-10), 2021.

4. Brooke, J., SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. In Patrick W. Jordan, B. Thomas, Ian Lyall McClelland and Bernard Weerdmeester (eds), Usability evaluation in industry, Taylor & Francis, London, 4-7, 1996.

Google Scholar

5. Finstad, K., Analogical problem solving in casual and experienced users: When interface consistency leads to inappropriate transfer, Human–Computer Interaction, 23(4), 381-405, 2008. doi:10.1080/07370020802532734.

Google Scholar

6. He, W. and Yang, X., "Artificial intelligence design, from research to practice", Proceedings of The International Conference on Computational Design and Robotic Fabrication (pp. 189-198), 2020.

Google Scholar

7. Ivory, M.Y. and Hearst, M.A., The state of the art in automating usability evaluation of user interfaces, ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 33(4), 470-516, 2001. doi:10.1145/503112.503114.

Google Scholar

8. Kellogg, W.A., "Conceptual consistency in the user interface: Effects on user performance", Proceedings of the Human–Computer Interaction–INTERACT'87 (pp. 389-394), 1987.

Google Scholar

9. Lu, Y., Zhang, C., Zhang, I. and Li, T.J.J., "Bridging the Gap between UX Practitioners' work practices and AI-enabled design support tools", Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts (pp. 1-7), 2022.

Google Scholar

10. McNutt, A., Stone, M.C. and Heer, J., "Mixing linters with GUIs: A color palette design probe", Proceedings of the IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 2024.

Google Scholar

11. Nielsen, J., "Usability inspection methods", Proceedings of the Conference companion on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 413-414), 1994.

Google Scholar

12. Pereira, R.M., Malucelli, A. and Reinehr, S., "From Real-Time Conversation to User Story: Leveraging Agile Requirements through LLM", Proceedings of the Simpósio Brasileiro de Engenharia de Software (SBES) (pp. 657-663), 2025.

Google Scholar

13. Simpson, N., Managing the use of style guides in an organisational setting: practical lessons in ensuring UI consistency, Interacting with Computers, 11(3), 323-351, 1999. doi:10.1016/S0953-5438(98)00069-1.

Google Scholar

14. Viswanathan, S. and Peters, J.C., "Automating UI guidelines verification by leveraging pattern based UI and model based development", Proceedings of the CHI'10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 4733-4742), 2010.

Google Scholar

15. Xu, Z., Li, Q. and Tant, S.H., "Understanding and Enhancing Attribute Prioritization in Fixing Web UI Tests with LLMs", Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation (ICST) (pp. 326-337), 2025.

Google Scholar

16. Yang, B., Xing, Z., Xia, X., Chen, C., Ye, D. and Li, S., "UIS-hunter: Detecting UI design smells in Android apps", Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 43rd international conference on software engineering: companion proceedings (ICSE-companion) (pp. 89-92), 2021.

Google Scholar

17. Zhao, D., Xing, Z., Chen, C., Xu, X., Zhu, L., Li, G. and Wang, J., "Seenomaly: Vision-based linting of GUI animation effects against design-don't guidelines", Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 42nd international conference on software engineering (pp. 1286-1297), 2020.

Google Scholar

PIDS App ServiceClick here!